Provenance and Purity: Nix programming language & Fixed-Output Flakes

← back to blogProvenance and Purity: Nix programming language & Fixed-Output Flakes

Before getting into this , let me explain what functional programming languages are :)

The wikepedia quotes - functional programming is a programming paradigm where programs are constructed by applying and composing functions. It is a declarative programming paradigm in which function definitions are trees of expressions that map values to other values, rather than a sequence of imperative statements which update the running state of the program.

Let’s see that visually , ive written some examples to help understand this better

Let me establish an important notion: defining components through functions that accept values for their variation points provides far greater flexibility than approaches where these variation points are bound using global variables.

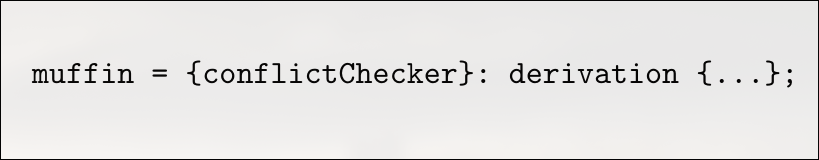

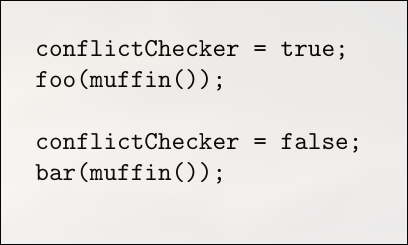

Imagine we have a library called muffin (YES) , it has several options built it , and one option called ” confict checker” is enabled . now imagine that this setting is important and it can change semantics . The point is that trying to make is a build with “conflict-checker” cannot be substituted by a build without “confict-checker” , and vice versa.

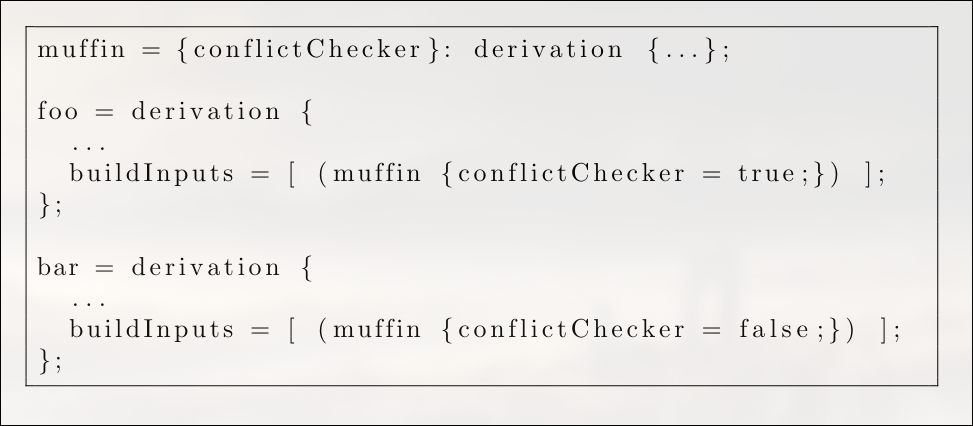

Now further adding to this lets say i have a component , consisting of two programs, foo and bar, that require the muffin library with and without “conflict-checker” respectively .

It’s very cutesey to model this in a purely functional langauge

I could just make a function for muffin which does so

We can now call this function twice with different values, in the derivations of foo and bar respectively:

Mhmm so how do we adress this issue moving forward ?

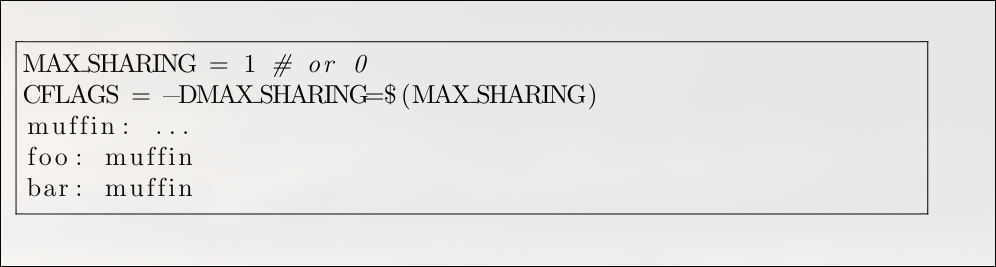

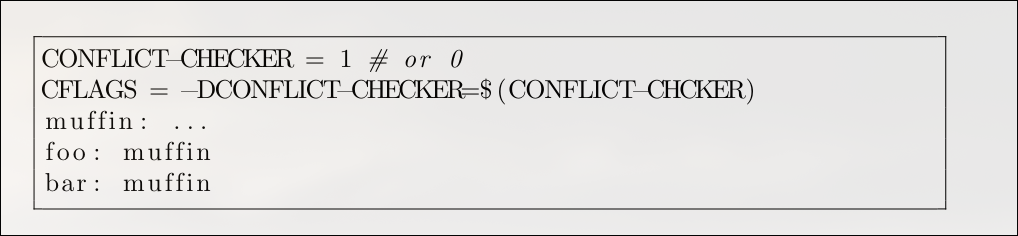

If the language were a Makefile-like declarative formalism, then

it would be quite hard to implement this example. Makefiles are a formalism to

describe the construction of (small-grained) components. Variability in a component is

typically expressed by setting variables globally before invoking make. For example, one might write:

A significant challenge with Make is building a component in multiple configurations at the same time. For example, it’s not obvious how to build both foo and bar with their different library variants in a single, clean process

When developers need to do this, they often resort to special workarounds. A common technique is to call make multiple times (recursively), passing different flags on each call and manually renaming the output files to avoid conflicts.

An imperative scripting language, however, would make this task more straightforward. A script written in that style might look like this

However, this imperative approach introduces the same classic problems found in general-purpose scripting. The biggest issue is that the order of execution is critical, which makes it difficult to know the exact configuration being passed to a build function like muffin() at any given moment.

While you can trace the logic in a trivial example, the complexity quickly becomes unmanageable as the build script grows with more functions, variables, and if/else branches. It’s important to note that this isn’t just a problem with global variables. Even if conflictChecker were a property of a muffin object, you would still need to track the program’s execution step-by-step to understand the object’s state when muffin() is called, which makes the whole build process hard to reason about :(

Laziness (JIT compilation)

Ok so a way to solve this would be to use a lazy language A key feature of a lazy language is that it only computes a value at the exact moment it’s needed. This property is incredibly powerful for a language used to describe software packages and systems.

Consider a typical flake.nix (ill explain this on the way but for now think of it as a substitute for a make file ) for a project. You can define a large and varied collection of outputs in that single file, such as:

-

packagesfor a web server and a command-line tool. -

devShellsfor your frontend and backend teams. -

nixosConfigurationsfor a production server and a local virtual machine.

Because the language is lazy, if you run a command like nix build .#server, Nix will only evaluate and build that specific server package and its dependencies. It completely ignores the definitions for the command-line tool, the development shells, and the other system configurations, saving a huge amount of time and resources. You can define an entire universe of components without paying the price for anything you don’t immediately use

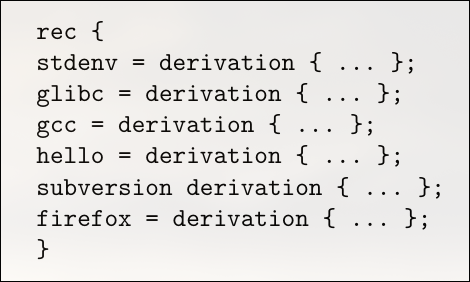

Since the language is lazy, the right-hand sides of the attributes will not be evaluated until they are actually needed, if at all.

For instance, if we install any specific component from this set, say,

nix-env -i hellothen only the hello value will be evaluated (although it may in turn require other values to be evaluated, such as stdenv).

Laziness also allows greater efficiency if only parts of a complex data structure are needed.

Take the operation:

nix-env -qawhich prints the name attribute of all top-level derivations in a Nix expression.

Laziness allows arguments to be passed to functions that may not be used is the main idea .

NIX FLAKES : )

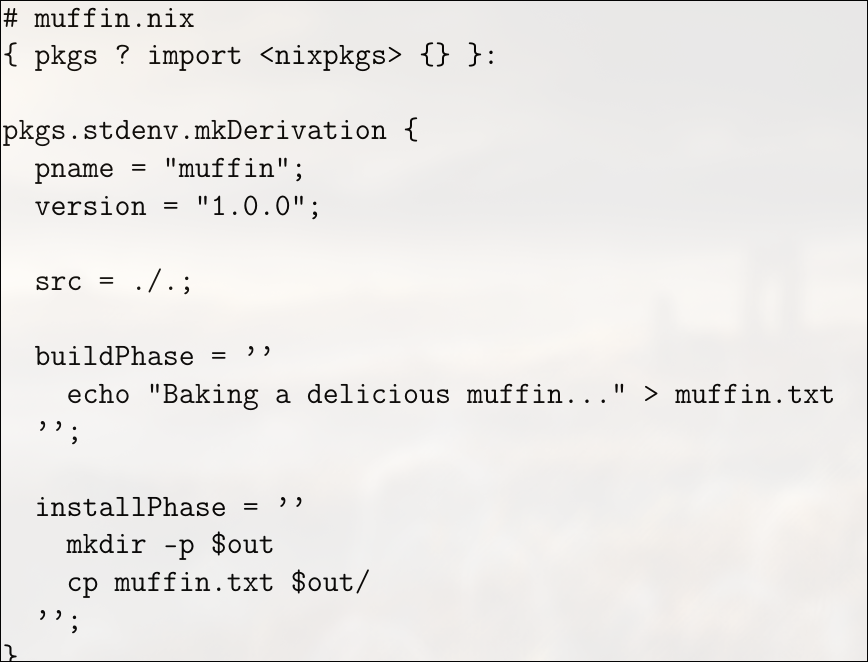

A Nix expression is code written in the Nix language that describes how to build or configure something, while a Nix file is a .nix file that contains one or more of these Nix expressions.

For example:

The first line, { pkgs ? import <nixpkgs> {} }:, defines a function that takes an argument named pkgs, which by default is set to the result of importing <nixpkgs>. This gives the expression access to the standard Nix package set, allowing the use of common utilities and build functions. The next expression, pkgs.stdenv.mkDerivation { ... }, declares a derivation, which is a build recipe describing how to construct a package. Inside this derivation, the attributes pname = "muffin"; and version = "1.0.0"; specify the package name and version. The src = ./.; line indicates that the source files for the package are located in the current directory, i.e., the same directory as the .nix file itself. The buildPhase section is a shell script that runs during the build process; in this case, it simply creates a file named muffin.txt containing the message “Baking a delicious muffin…”.

Hopefully this muffin example gave an idea about how nix expressions work , just the syntax tho :3

So what the fuck are flakes now ?

The basic idea of flakes isn’t that complicated, but it does require a little bit of basic understanding of the nix programming language(try making your own .nix expression adhering to the muffin example the nix error checker is very nice and :) ) . A flake.nix file is an attribute set with two attributes called inputs and outputs. The inputs attribute describes the other flakes that you would like to use; things like nixpkgs or home-manager. You have to give it the url where the code for that other flake is, and usually people use GitHub. The outputs attribute is a function, which is where we really start getting into the nix programming language. Nix will go and fetch all the inputs, load up their flake.nix files, and it will call your outputs function with all of their outputs as arguments. The outputs of a flake are just whatever its outputs function returns, which can be basically anything the flake wants it to be. Finally, nix records exactly which revision was fetched from GitHub in flake.lock so that the versions of all your inputs are pinned to the same thing until you manually update the lock file.

Now, I said that the outputs of a flake can be basically anything you want, but by convention, there’s a schema that most flakes adhere to. For instance, flakes often include outputs like packages.x86_64-linux.foo as the derivation for the foo package for x86_64-linux. But it’s important to understand that this is a convention, which the nix CLI uses by default for a lot of commands. The reason I consider this important to understand is because people often assume flakes are some complicated thing, and that therefore flakes somehow change the fundamentals of how nix works and how we use it. They don’t. All the flakes feature does is look at the inputs you need, fetch them, and call your outputs function. It’s truly that simple. Pretty much everything else that comes up when using flakes is actually just traditional nix, and not flakes-related at all.

Enough yapping , lets see an actual flake now which i use for my hyprland ecosystem

This flake defines a NixOS system configuration using the experimental flakes system. At its core, the flake is a self-contained directory that includes a flake.nix file, specifying inputs, outputs, and the system it builds. The flake begins with a description field, giving a human-readable label for the configuration, in this case "My NixOS configuration".

{

description = "My NixOS configuration";

inputs = {

nixpkgs.url = "github:nixos/nixpkgs/nixos-unstable";

caelestia-shell = {

url = "github:caelestia-dots/shell";

inputs.nixpkgs.follows = "nixpkgs";

};

};

outputs = { self, nixpkgs, caelestia-shell, ... }@inputs:

let

system = "x86_64-linux";

pkgs = nixpkgs.legacyPackages.${system};

in {

nixosConfigurations.nixos = nixpkgs.lib.nixosSystem {

inherit system;

modules = [

./configuration.nix

# Inline module to add Caelestia Shell with CLI

{

environment.systemPackages = [

(caelestia-shell.packages.${system}.with-cli)

];

}

];

specialArgs = { inherit inputs system; };

};

};

}The inputs section declares dependencies required by this flake. It includes nixpkgs, referencing the unstable branch of the official NixOS package collection from GitHub. It also includes a custom flake, caelestia-shell, which represents a shell environment maintained externally. To ensure consistency, caelestia-shell is configured to use the same nixpkgs version as the main flake via inputs.nixpkgs.follows = "nixpkgs". This prevents version mismatches between package sets when building the system.

The outputs function defines what this flake produces. It takes all declared inputs and makes them available for use within the flake. Inside outputs, the system variable is set to "x86_64-linux", and pkgs is assigned the corresponding nixpkgs package set for that system. This allows the flake to reference packages specific to the target architecture during system construction.

Within the outputs, a NixOS configuration called nixos is defined using nixpkgs.lib.nixosSystem. This function builds a fully specified NixOS system. The configuration uses two modules: the main configuration.nix file, which contains standard user-defined system settings, and an inline module that adds the Caelestia Shell CLI to environment.systemPackages. This ensures that the shell is globally available on the system. The specialArgs attribute passes inputs and system to all modules, allowing modules to reference flake inputs or architecture-specific values if necessary.

Should I use flakes in my project?

I think that Nix flakes have some considerable benefits, such as:

- Convenient pinning of evaluation-time dependencies

- Eliminating pointless rebuilds of code by only including tracked files in builds

- Making Nix code, on average, much more reproducible by pervasive pinning

- Allegedly caching evaluation

- Possibly making Nix easier to learn by reducing the amount of poking at strange attribute sets and general

NIX_PATHbrokenness

The Nix language, along with functions and nixpkgs utilities, provides a powerful composition primitive. In my experience, these tools are especially useful in monorepos, where different parts of a project need to be assembled modularly and flexibly. Functions allow parametrization and reuse, while nixpkgs provides a rich set of prebuilt packages and build utilities that make composing systems straightforward.

While flakes are a useful entry point for projects and make dependency management, version control integration, and lockfiles easy, they are not always the most practical tool for composing software. In medium-sized projects, locking subproject dependencies can be undesirable, and for very small utilities, writing a separate flake.nix feels like unnecessary overhead. In very large projects, like nixpkgs itself, managing everything through flakes would make the flake.nix file enormous and unwieldy, containing potentially hundreds of thousands of inputs.

Flakes also have limitations when it comes to flexible builds. They provide minimal support for runtime configuration, and customizing builds often requires awkward workarounds like --override-input. This means all build variants must either be anticipated ahead of time or implemented using traditional Nix primitives such as functions, overlays, and modules. Flakes are also difficult to use for cross-compilation, since there is no straightforward way to specify a target architecture, making constructs like packages.${system} unusable in that context.

Because of these constraints, even in a flakes-based setup, it is often more effective to rely on traditional Nix composition primitives to assemble software both in the small and in the large. A flake can then serve mainly as an entry point and a way to fetch dependencies needed for evaluation, while build-time dependencies can be handled through primitives like pkgs.fetchurl or pkgs.fetchFromGitHub. To expose multiple configurations of a program, it is common to write a lambda that accepts configuration parameters and call it multiple times to produce different outputs. This approach separates configuration capability from specific build definitions, avoiding the need to embed complex logic in the flake itself.

One of the most distinctive features of Nix is that it is Turing complete. While this can make static analysis difficult, it also provides immense flexibility: packages can be patched programmatically, configurations can be generated dynamically, and arbitrary files can be read and processed at build time. Because Nix is a functional language, its fundamental composition primitive is the function. Even constructs like NixOS modules or overlays are functions that can be imported, partially applied, or reused across projects. In practice, modules are usually imported by path rather than generated dynamically, because imports are deduplicated by filename.

flake.nix (default.nix, shell.nix) in project directories

These are developer packaging of projects: pinned tool versions, not caring as much about unifying dependencies with the system, etc. To this end, they provide dev shells to work on a project, and are versioned with the project. Additionally they may provide packaging to install a tool separately from nixpkgs.

There are a couple of things that make these notable compared to the packaging one might see in nixpkgs:

- In nixpkgs, more build time is likely tolerated, and there is little desire to do incremental compilation. Import from derivation is also banned from nixpkgs. For these reasons, packaging outside of nixpkgs likely uses different frameworks and other similar tools that reduce the burden of maintaining Nix packaging or speed up rebuilds.

- It’s versioned with the software and so more crimes are generally tolerated: one might pin libraries or other such things, and update nixpkgs infrequently.

- They include the tools to work on a project, which may be a superset of the tools required to build it, for example in the case of checked-in generated code or other such things.

- They may include things like checks, post-commit hooks and other project infrastructure.

Shells are just made of environment variables and (without building one at least) don’t create a single bin folder of all the things in the shell, for instance. Also, since they are made of environment variables, they don’t have much ability to perform effects such as managing services or on-disk state.

Use this for tools specific to one project, such as compilers and libraries for that project. Depending on taste and circumstances, these may or may not be used for language servers. Generally these are not used for providing tools like git or nix that are expected to be on the system, unless they are required to actually compile the software.

(Note that for Bad Reasons, nix-shell -p is not equivalent to nix shell: the latter does not provide a compiler or stdenv as would be necessary to build software. The technical reason here is that nix shell constructs the shell within C++ code in Nix, whereas nix-shell -p is more or less nix develop on a questionable string templated expression involving pkgs.mkShell)

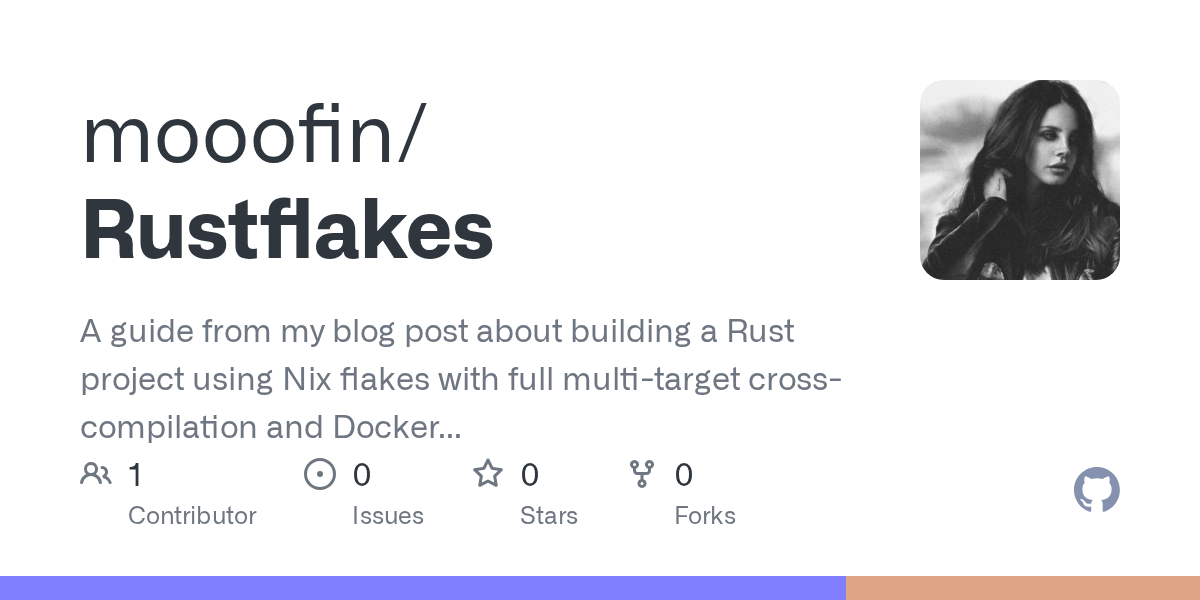

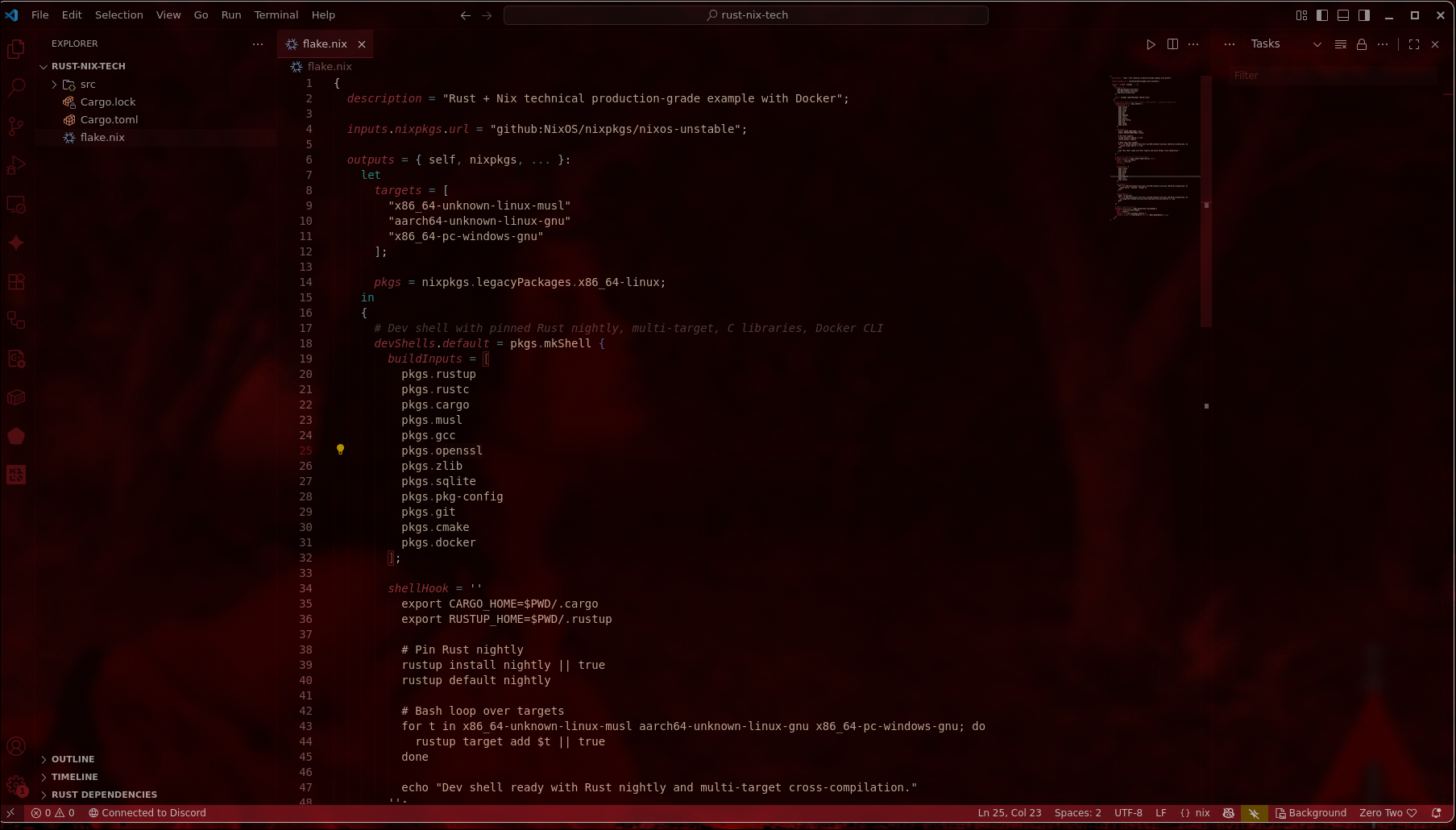

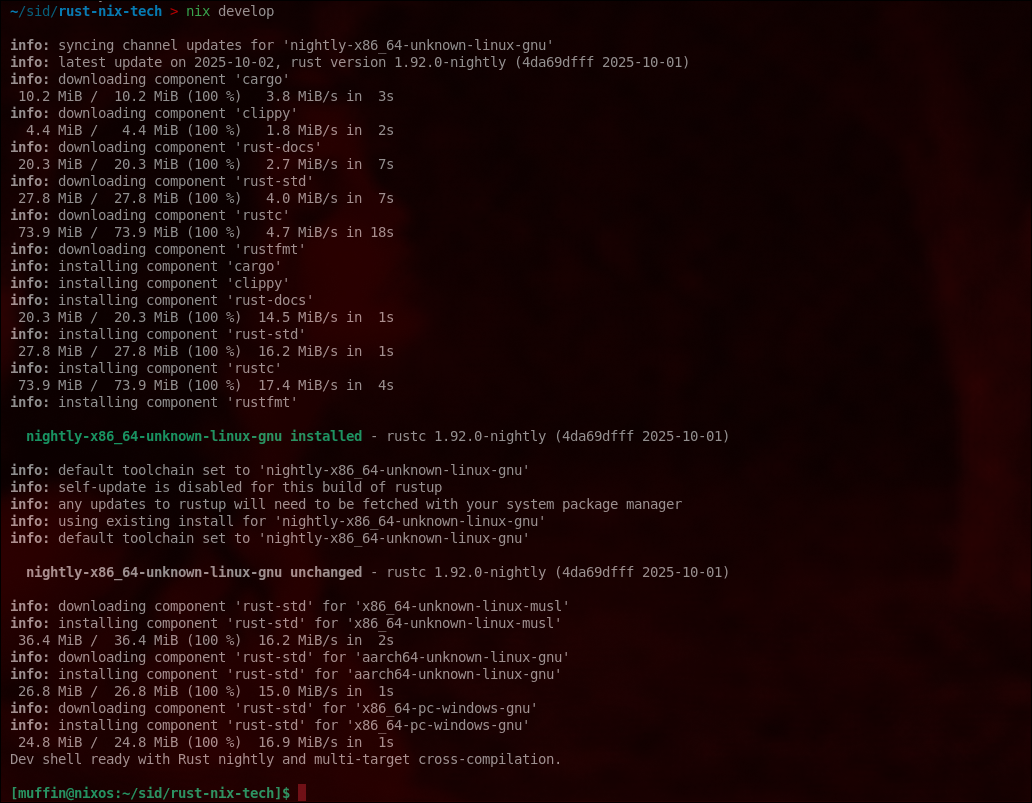

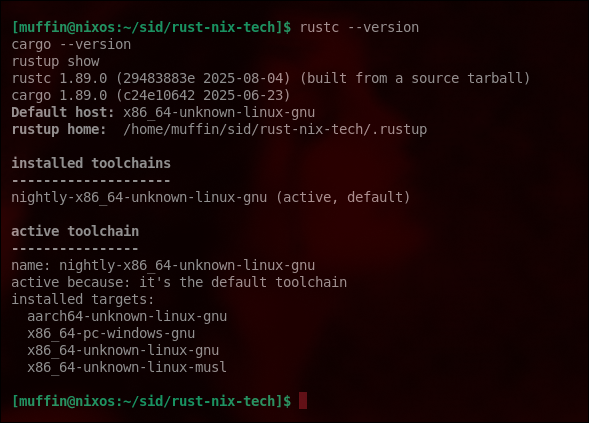

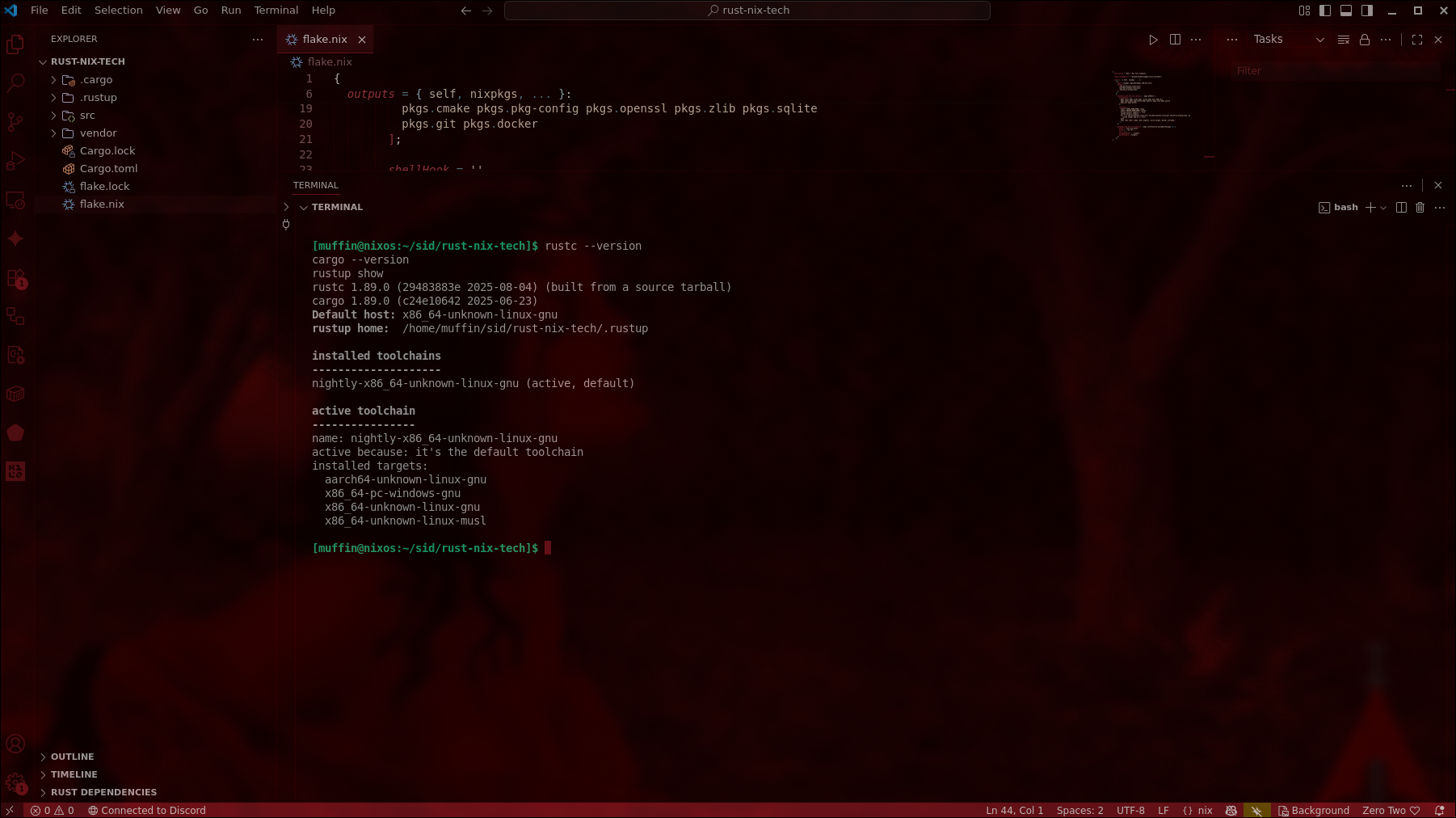

To demonstrate this i’ve written a Rust + Nix project with multi-target cross-compilation and Docker support

In this guide, we’ll learn how to build a Rust project using Nix flakes with full multi-target cross-compilation and Docker image generation. Instead of relying on local toolchains or ad-hoc scripts, we’ll declare everything Rust versions, dependencies, targets, and environment inside a single flake.nix file. This gives us a fully reproducible, isolated, and declarative setup. By the end, you’ll understand how Nix ensures consistent builds across machines, how it provisions multiple targets like x86_64-unknown-linux-musl, aarch64-unknown-linux-gnu, and x86_64-pc-windows-gnu, and how to package your Rust binary inside a lightweight Docker image all from one flake-based configuration

Why Use Nix Flakes for ANY Projects?

When building Rust applications, especially for production or cross-platform distribution, you face several common challenges. Different machines often have different Rust versions installed via rustup, leading to toolchain drift. Native libraries like OpenSSL vary wildly across distros, creating system dependency chaos. Setting up Windows or ARM targets requires painful manual linker configuration. Build scripts that work perfectly on your local machine mysteriously break in CI environments, and multi-stage Dockerfiles end up duplicating build logic in confusing ways.

Nix Flakes Solution:

With the Rustflakes approach, you get a much cleaner solution. One flake.nix file becomes your single source of truth, declaring the Rust version, all system dependencies, and build targets in one place. Builds are hermetic—they don’t rely on whatever happens to be installed on your host system. Cross-compilation becomes trivial: just add a target to flake.nix and run nix build .#windows or .#aarch64. You even get Docker images for free, generated directly from Nix derivations. Since dependencies are vendored in vendor/, builds work offline without network access.

This makes Rustflakes particularly valuable for teams needing consistent builds across developer machines and CI, projects targeting multiple platforms like Linux, Windows, and ARM, embedded or IoT applications requiring specific toolchain versions, and security-conscious environments requiring reproducible builds.

The repository demonstrates this with working examples for x86_64-linux, aarch64-linux, and x86_64-windows targets, all built from the same declarative configuration.

Building the Project

Let’s walk through using this Nix-based Rust project:

Entering the environment gives us

-

If you want to run a simple stand-alone binary just once, use nix run. E.g.

nix run nixpkgs#tree(the command will have to live in$out/bin/<pname>) (ormeta.mainProgram, if that exists) -

To pass it arguments, use

--or your flags will be interpreted bynix run, not passed to the command. E.g.nix run nixpkgs#tree -- -a -

To put that in the PATH of your current shell, temporarily, so you can run it a bunch of times today:

nix shell nixpkgs#ffmpeg. Tip: to enable multiple programs:nix shell nixpkgs#{ffmpeg,tree,imagemagick}. -

Maybe your desired binary exists in

$out/bin, but has a different name? This is an odd one:nix shell nixpkgs#postgresql --command psql ...(extra odd: you don’t need to use--to separate program args from nix args.) (I understand the “why” behind this, but I hate it. The newnixcommand was supposed to solve the counterintuitive UI problem, but here we are, back to square 1. -

Say you want to “build” a derivation, you use

nix build, although if it’s available in a binary cache it will just fetch it from there:nix build nixpkgs#imagemagick. Now you have it in your/nix/store, and a symlink to that path in./result. -

Sometimes I just want to build something and print the path to stdout, without actually creating a link in

/nix/store. Combine two flags:nix build nixpkgs#imagemagick --print-out-paths --no-link.-

I use that to do stuff like this:

$ nix run nixpkgs#tree -- $(nix build nixpkgs#imagemagick --print-out-paths --no-link)/bin. -

Or this, on mac:

open $(nix build nixpkgs#grandperspective --print-out-paths --no-link)/Applications/* -

You can see how

nix runreally is just syntactic sugar for$(nix build --no-link --print-out-paths <deriv>)/bin/<deriv.meta.mainProgram or deriv.pname>(sort of)

-

But my all time favourite is nix develop: it plops you in a build shell for a derivation. This means you can pretend you are the nix builder, locally. Including fetching the source!

E.g., to build sbcl (the lisp compiler) locally, without installing anything else nor even downloading the source, just:

$ cd $(mktemp -d)

$ nix develop nixpkgs#sbcl

$ unpackPhase

$ cd *

$ patchPhase

$ eval "$buildPhase"

$ .... debug problems here...I think this is very neat.

SO to summarise

-

nix shell: alters your shell. Use it when you want to use a package.

-

nix develop: for developing something. Only use it when you are developing a package.

-

nix run: one-off running of programs.

-

nix build: ensure a derivation is available in your /nix/store. Either download or build. Optionally: create symlink in ./result, and/or print the output path to stdout, and/or print build noise to stderr (

--print-build-logs).

Coming back to the project we can see that muhehe

Let’s break down what the nix approach using flakes solves here , ill adress the main things in packaging

Let’s break down what the nix approach using flakes solves here , ill adress the main things in packaging

1. Reproducibility

Normally, if you just run cargo build, your binary depends on several local factors: the version of Rust installed on your machine, the versions of system libraries like libssl or libsqlite, and the state of your local Cargo.lock. With Nix, the build becomes fully reproducible. It uses a specific Rust toolchain (nightly in our example), relies on vendored dependencies in the vendor/ directory, and incorporates all libraries declared in the flake.nix dev shell. The result is that anyone on any machine with Nix installed can build the exact same binary, eliminating the common “works on my machine” problems.

2. Isolation

Nix builds everything inside a sandbox located in /nix/store, which prevents accidental dependencies on files outside the project or on system-installed libraries or Rust versions. This isolation ensures that builds are deterministic and safe, making it ideal for continuous integration and deployment pipelines.

3. Cross-compilation

Building for multiple targets such as Linux, ARM, or Windows normally requires installing Rust targets manually and configuring toolchains and linker flags. With Nix, you can declare all your targets in flake.nix for example, x86_64-unknown-linux-musl, aarch64-unknown-linux-gnu, and x86_64-pc-windows-gnu. Nix automatically sets up all the required compilers and Rust standard libraries for these targets, making cross-compilation seamless.

4. Automation and Declarative Builds

Using Nix eliminates the need for manual scripts like build-all.sh. Everything is declarative in flake.nix: the dev environment is set up automatically with nix develop, binary builds happen with nix build .#default, and cross-compilation targets are handled automatically. This declarative approach makes your Rust project fully CI/CD-ready with zero surprises.

Wrapping it up

A Language for Builders

We need to find a better way to write builders. Shell scripts are simply not a good language for this purpose. The Unix shell is quite good as component glue which is what we use it for but it is not safe enough. It is, in fact, virtually impossible to write “correct” shell scripts that do not fail unexpectedly for banal reasons on certain inputs or in certain situations.

Problems with Shell Scripts

Here are some of the main problems in the language:

-

Variable interpolation (e.g.,

$foo) happens by default.

This causes most shell scripts to fail on file names that contain spaces or newlines.

The same applies to automatic globbing (expansion of special characters such as*). -

Undefined variables do not signal an error.

-

Non-zero exit codes from commands are ignored by default.

Worse, it is extremely hard to catch errors from the left-hand sides of pipes.

In fact, the whole Unix toolchain is not conducive to writing correct code:

-

Command-line arguments in Unix are usually overloaded.

For example, there is an ambiguity in most Unix tools between options and file names starting with a dash. -

The pipe model assumes that all tools read and write flat text files without a well-defined structure.

This makes it hard to extract relevant data in a structured way. Typically, regular expressions in conjunction with tools likegrep,sed,awk, andperlare used to extract data but this tends to be brittle. The regular expressions hardly ever cover all possibilities. -

Similarly, the fact that options are flat strings makes it hard to pass structure, necessitating escaping.

For instance, the commandgrep -q "$filename"to see whether a certain file name occurs in a list fails to account for the fact thatgrepinterprets some characters in$filenameas regular expression meta-characters.

The Problem of Eliminating “Bad” Components in a Purely Functional Model

While the purely functional model used by Nix offers strong guarantees of reproducibility and non-interference, it introduces a unique challenge:

How can we ensure that all uses of a certain “bad” component such as one containing a security vulnerability have been fully eliminated?

Consider a scenario where a fundamental dependency, such as Zlib, is discovered to contain a critical security flaw.

Because Zlib is widely used by many other components and applications, we must guarantee that every package depending on the vulnerable version is replaced with one built against a patched version.

In principle, we might attempt to update everything using a command like:

nix-env -u "*"However, this approach is not guaranteed to remove all vulnerable components especially if some were installed from arbitrary third-party sources outside of Nixpkgs.

This limitation arises from the very non-interference property that makes Nix functional and reproducible: each component is built in isolation, without being globally overwritten or modified in place. While this ensures determinism, it also means that outdated or insecure builds can persist if not explicitly replaced.

Toward a Solution

To address this, the system needs a generic detection mechanism that can identify the presence or usage of “bad” components.

Such a mechanism would rely on a blacklist describing known-vulnerable packages or derivations. The build system could then trace dependency graphs and flag (or prevent) any components that still depend on blacklisted items.

This approach ensures that security updates are systematic and verifiable, preserving the advantages of the functional model while adding safety guarantees against vulnerable dependencies.

In essence, while Nix’s functional model prevents uncontrolled interference, it also prevents automatic global replacement of insecure components. The solution lies in explicit detection and tracing mechanisms, guided by a blacklist, that can systematically ensure the removal and replacement of all affected packages combining deterministic builds with reliable security assurance.

Some honest thoughts

Contrary to popular believe, you don’t need to learn the nix language to use nix. From your perspective, nix can be glorified json for configuring your system. There is much more to the programming language that you probably won’t ever have to care about.

I don’t think NixOS is intrinsically more work or more complicated than Debian. It can be if you are coming from a traditional distro or if your specific use case is not supported well. E. g. setting up a web server, a firewall or other system components is much easier in NixOS. Getting some random python package working however can be a big pain. If you use popular software you should be good.

I’d argue using NixOS is more involved at the beginning but gets much less involved after you set things up as generally things don’t break. Once in a while you get a deprecation message and may need to adjust your configuration - that’s it.

I find myself however stumbling upon better ways of configuring my system and steadily improving my set up. I believe I wouldn’t be doing that on a traditional distro so much because it would be much harder to do these things while keeping state. So if you are a perfectionist or an enthusiast you will probably spend more time just because it’s much more fun :3