The Deployment Gap: From Your Machine to Theirs

← back to blogThe Deployment Gap: From Your Machine to Theirs

So you’ve built some amazing software. It runs beautifully on your machine,flawless, fast, and bug-free. You package it up, send it out into the world, and then the emails start pouring in: “It crashes on startup.” “I’m getting a weird error.” “It doesn’t work.""Your SAAS sucks ” .

How is this possible? Your software was perfect.(atleast the LLM said so)

This frustrating gap between your machine and a user’s machine is the central problem of software deployment. It can be traced back to two things mostly : environment issues and manageability issues.

I. Environment-Induced Failures

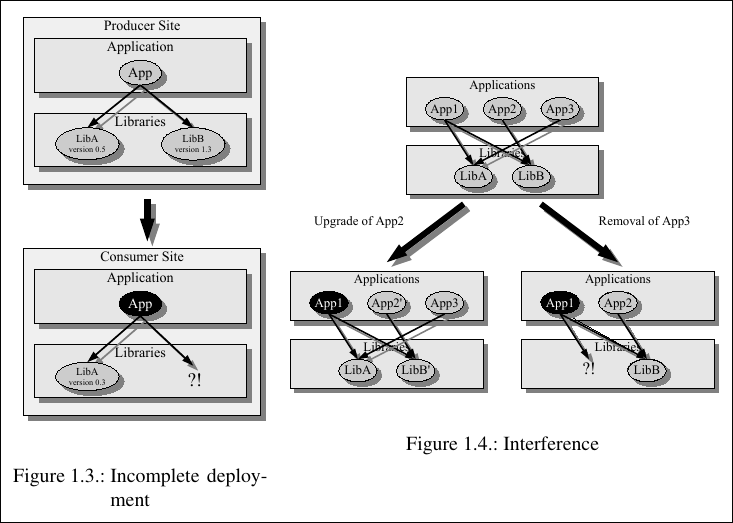

These failures arise from mismatches between the development environment and the user’s environment. A program that depends on a certain library version may encounter errors when that library is missing or replaced with a different one. An application tested on one operating system may falter on another due to differences in kernels, filesystems, or system calls. Even small variations in system state environment variables, permissions, locales, or network configurations can derail execution. (flashbacks of setting up GCC in codeblocks :( )

The troubling aspect of these failures is that they occur even when the application code itself is correct. The software logic is sound, yet the surrounding environment conspires to break it.

II. Lifecycle Management Deficiencies

Deployment issues extend beyond installation into the ongoing care and feeding of software. Updates that are not atomic may leave a program half-upgraded and unusable, with no reliable way to roll back. Uninstallations are often incomplete, scattering configuration files and leftover data across the system. Over time, these remnants accumulate into cruft that burdens stability and maintainability.

Perhaps most notoriously, multiple applications may demand different, mutually incompatible versions of the same shared library. When this conflict occurs, one program’s gain is another’s crash, leaving the system as a whole unstable.

The System as a Solved Graph

The Architectural Imperative of the Linux Package Manager

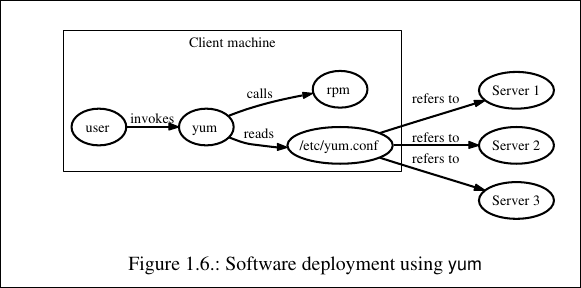

If the deployment gap exposes the problems, then the package manager represents one of the most elegant solutions devised to address them. Its central role in Linux and other Unix-like systems is no accident. It arises from a deep architectural philosophy: one that concerns how software is stored and how it is constructed.

I. The Unified Filesystem

The first principle of this philosophy is the unified filesystem, sometimes described as a global namespace. Rather than bundling each application with its own set of dependencies, Unix integrates all components into a shared hierarchy. Executables are placed in /usr/bin, libraries in /usr/lib, and configuration files in /etc.

This design treats the operating system as a single, coherent whole rather than a loose collection of isolated applications. Yet such coherence introduces risk. Without a mechanism to govern the placement and compatibility of files, the system would quickly collapse into chaos. The package manager assumes this responsibility, acting as the arbiter that maintains order within the shared space.

II. A Commitment to Modularity

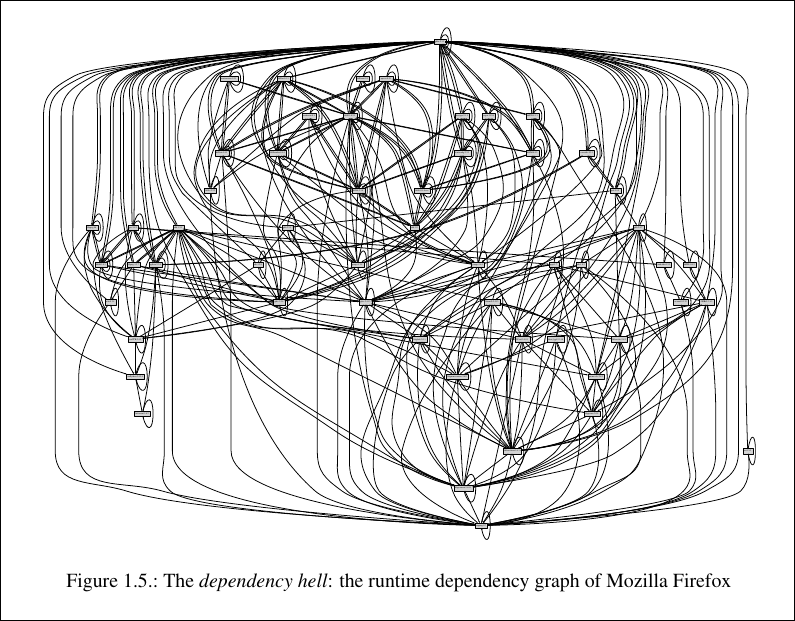

The second principle is a commitment to modularity and fine-grained reuse. Applications are rarely monolithic; instead, they are typically small executables that rely on dynamically linked libraries for most of their functionality. A single library may serve dozens of programs, and improvements to that library immediately extend to all of them.

This design maximizes efficiency but also creates complexity. The system is no longer a collection of independent parts but a tightly woven dependency graph. Keeping this graph consistent, valid, and conflict-free is far too intricate for manual intervention.

Here again the package manager proves indispensable. It resolves dependencies, prevents conflicts, and ensures that the modular structure of the system remains intact.

The Nix Model: A Functional Approach to Deployment

In our previous discussion, we examined the core architectural challenges of traditional Unix-like systems: the potential for chaos in shared global namespaces and the complex web of fine-grained dependencies. These are not minor issues; they are fundamental problems that most deployment tools merely attempt to contain.

This brings us to Nix, a system designed from first principles to solve these problems directly. It doesn’t just manage the complexity ,it eliminates it by introducing a different, more robust paradigm: the purely functional deployment model.

The Core Idea: Software as a Pure Function

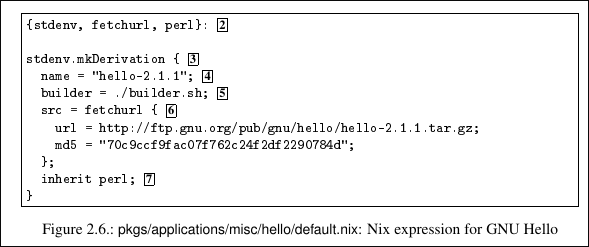

The central innovation of Nix is deceptively simple. Every piece of software, or “component,” is stored in its own unique directory within a special location called the Nix store (/nix/store). The clever part is the name of that directory. It isn’t just firefox-1.0.4; it’s a path that includes a cryptographic hash derived from every single input used to build that component-the source code, its dependencies, the compiler flags, everything.

A typical path looks like this:

/nix/store/rwmfbhb2znwp…-firefox-1.0.4

This means that if even a single bit changes in any of the inputs, the resulting hash will be different, and the component will be stored in a different location. This enforces the core principle of the functional model: a component is uniquely and completely defined by the inputs used to create it. Think of it like a mathematical function: build(inputs) = output. The same inputs will always produce the exact same output.

The Practical Consequences of a Functional Model

This elegant idea has profound consequences that directly address the traditional deployment issues. The long list of contributions from the Nix thesis can be understood as the practical benefits of this core design.

First, it provides unparalleled reliability and consistency. Because every component lives in isolation in its own hashed directory, there are no undeclared dependencies and version conflicts are impossible. Firefox built with one version of a library and a text editor built with another can coexist perfectly on the same system, as they occupy entirely different paths in the Nix store. The problems of a shared /usr/lib are simply sidestepped.

Second, it enables bulletproof operations. When you update your system, Nix builds the entire new configuration on the side without touching your running system. The switch to the new version is atomica single, instantaneous operation. If you don’t like the update, rollbacks are equally trivial and fast, as the old configuration is still present and untouched. The risk associated with a traditional, stateful upgrade process is eliminated.

Finally, the model offers immense flexibility and power. Nix uses a lazy, purely functional language to describe how to build software, which allows for expressing complex configurations and variations in an elegant way. It seamlessly blends source and binary deployment; if a pre-built binary matching a hash exists, Nix downloads it as an optimization. If not, it can build it from source. This model is so robust that it extends beyond simple package management to orchestrating entire services, implementing build farms for continuous integration, and even acting as a superior replacement for build tools like Make.

Inside the Nix Store: A World Without Conflicts

In the last article, we introduced Nix’s purely functional model for software deployment the idea that a piece of software should be a predictable output derived from a set of known inputs. But how does Nix enforce this principle at a technical level?

The answer lies in a special directory and a clever use of cryptography. Welcome to the Nix store.

The Anatomy of a Store Path

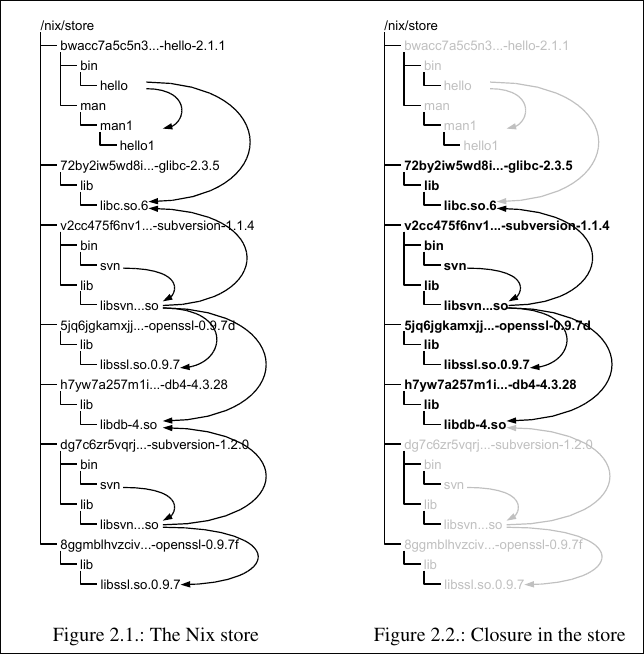

At its core, the Nix store is simply a directory, usually located at /nix/store. Inside this directory, every piece of software which Nix calls a component lives in its own isolated subdirectory.

The most notable feature, and the secret to Nix’s power, is the naming convention for these subdirectories. A component isn’t just named hello-2.1.1. Instead, it has a long, unique name called a store path:

/nix/store/bwacc7a5c5n3qx37nz5drwcgd2lv89w6-hello-2.1.1

That long string of characters is a cryptographic hash-a unique fingerprint computed from every single input used to build the component. This includes:

-

The source code itself.

-

The build scripts.

-

All build-time dependencies, like compilers and libraries.

-

Even the configuration arguments passed to the build.

If you change even a single byte in any of those inputs, the hash changes, and the component is installed to a completely new path. This single mechanism provides two foundational guarantees that solve the majority of problems in traditional deployment systems.

Pillar 1: Total Isolation, Zero Interference

Because every component’s identity is tied to the exact hash of its inputs, no two distinct components can ever occupy the same path. A program built against one version of a library will have a different hash than the same program built against a newer version.

This provides perfect isolation. You can have two versions of the same application, or two applications that depend on conflicting versions of a library, installed side-by-side without any interference. When you “upgrade” a component in Nix, you aren’t performing a destructive action. The new version is simply built and placed at a new path, leaving the old one entirely untouched. This is what makes upgrades and rollbacks not just safe, but trivial.

Pillar 2: Forced Honesty, Perfect Dependencies

The second, equally powerful guarantee is the prevention of undeclared dependencies. In a traditional system, a build script might look for a library like libssl in a global location like /usr/lib. If it finds it, the build succeeds, but that dependency might never be formally recorded. The program “works on your machine” but fails on another where that library is missing.

Nix solves this by eliminating global locations for dependencies. The Nix store is the only place to look. When building a component, the environment is scrubbed clean. The only way for a build process to find a library like OpenSSL is if its full, unique store path (e.g., /nix/store/5jq6jgkamxjj...-openssl-0.9.7d) is explicitly passed as an input.

Mechanism for Component Isolation

The Nix deployment model guarantees component isolation through a recursive hashing scheme. The store path of any given component is derived from a cryptographic hash of all inputs to its build process. This hash is computed recursively, meaning it incorporates the hashes of all build-time dependencies. The result is a unique identifier for a specific component configuration. Any modification to a component or its dependencies, however minor, alters the hash and thus generates a new, distinct store path. Consequently, the installation or removal of one component configuration has no effect on any other.

Non-Destructive Operations

This architecture ensures that all operations are non-destructive. For example, consider two versions of Subversion, where version 1.2.0 depends on a newer version of OpenSSL than its predecessor. The installation of Subversion 1.2.0 results in the addition of both the new Subversion and the new OpenSSL to the Nix store, each at a new, unique store path. The prior installation of Subversion and its corresponding OpenSSL dependency remain in the store, unaltered and fully functional. The old application continues to reference the old library, completely insulated from the new installation.

Dependency Propagation and Immutability

Changes propagate deterministically through the dependency graph. An update to a foundational library, such as GTK, will change its hash. This change recursively propagates to every component that depends on GTK, such as Firefox, which will in turn be rebuilt and assigned a new store path. Components that do not have a dependency on GTK, such as Glibc, are unaffected.

A critical aspect of this model is the immutability of components. Once a component is built and placed in the store, it is marked as read-only and is never modified. An “upgrade” is not a modification but the creation of a new component. This directly mirrors the principles of purely functional programming, where the output of a function is determined exclusively by its inputs. In Nix, the contents of a component are determined exclusively by its build-time inputs, providing a strong guarantee of non-interference.

A solved problem

Traditional package managers, born from the Unix philosophy o f shared, modular components, brought order to the chaos but never eliminated the underlying fragility. They manage the state, but the state remains mutable and prone to entropy.

Nix represents a paradigm shift. It reframes deployment not as a series of imperative actions to be performed, but as a declarative goal to be achieved. By adopting a purely functional model, Nix treats software and entire system configurations as immutable, reproducible values. The cryptographic hash is not just a clever trick; it is the mechanism that provides a mathematical guarantee of consistency-a guarantee that traditional systems simply cannot offer.

This approach transforms the fragile art of system administration into a solved engineering problem. It provides a foundation for truly reliable, reproducible, and robust systems, moving us beyond simply managing complexity and toward eliminating it altogether.