Onapookkalam / ഓണപ്പൂക്കളം - DFIR report

← back to blogOnapookkalam Challenge Writeup

Challenge Overview

While preparing for Onapookkalam, notes were recorded on a mobile device. The phone was suspected to be tampered with, potentially having data modified or deleted.

Objectives:

- Note Retrieval: Extract specific information from saved notes (flagPart1)

- Database Analysis: Identify a specific string that was modified and deleted from Realm DB (flagPart2)

Required Output Format: flag{flagPart1_flagPart2}

Investigation Process

Initial File Extraction

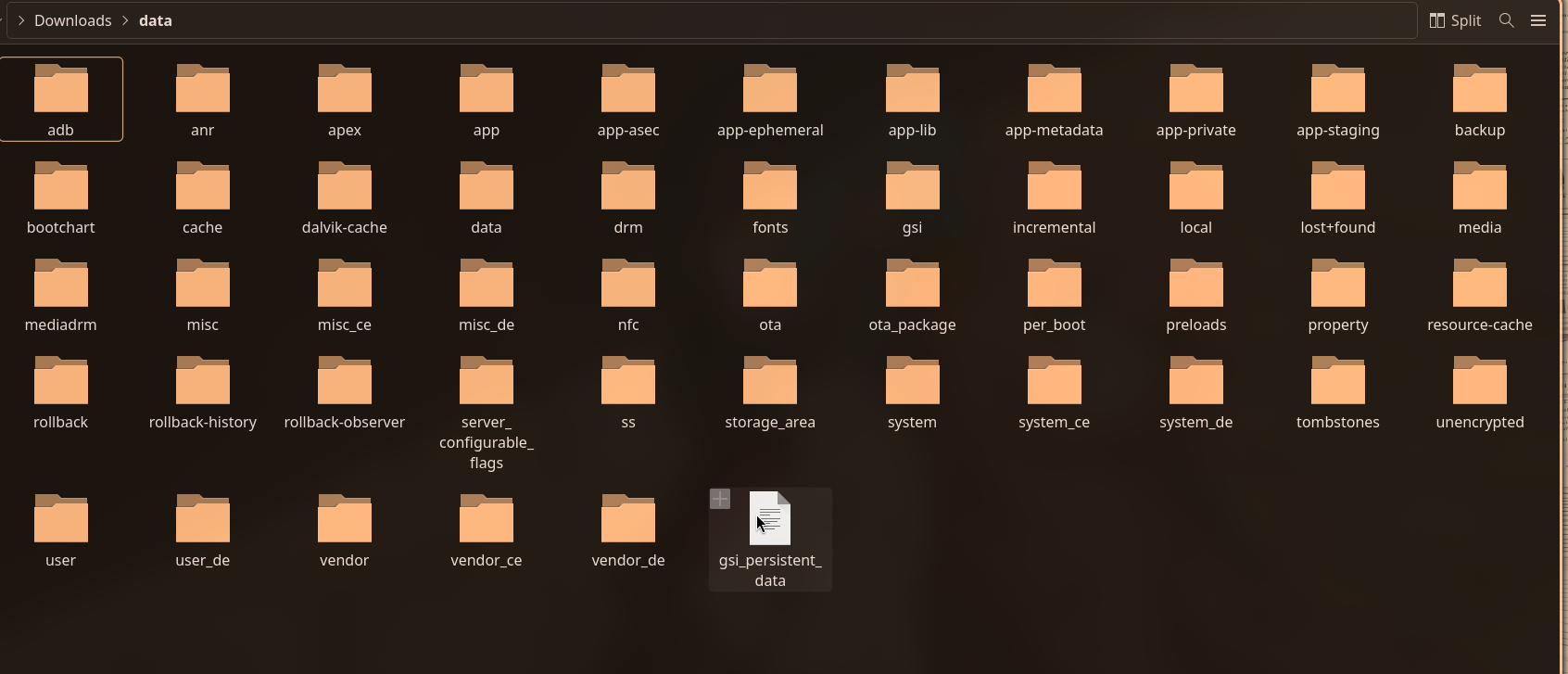

After extraction, numerous files were discovered:

Notes Recovery

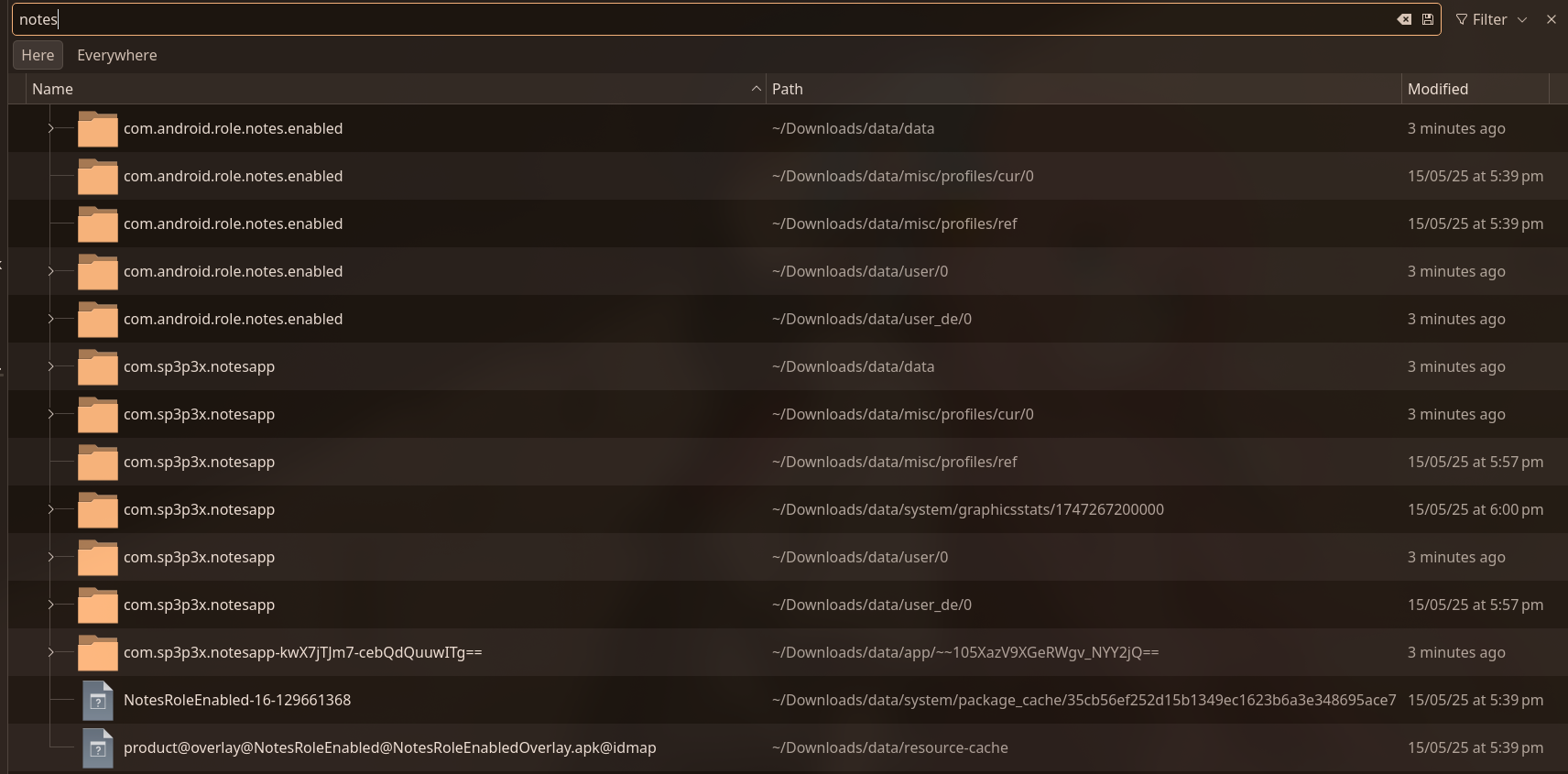

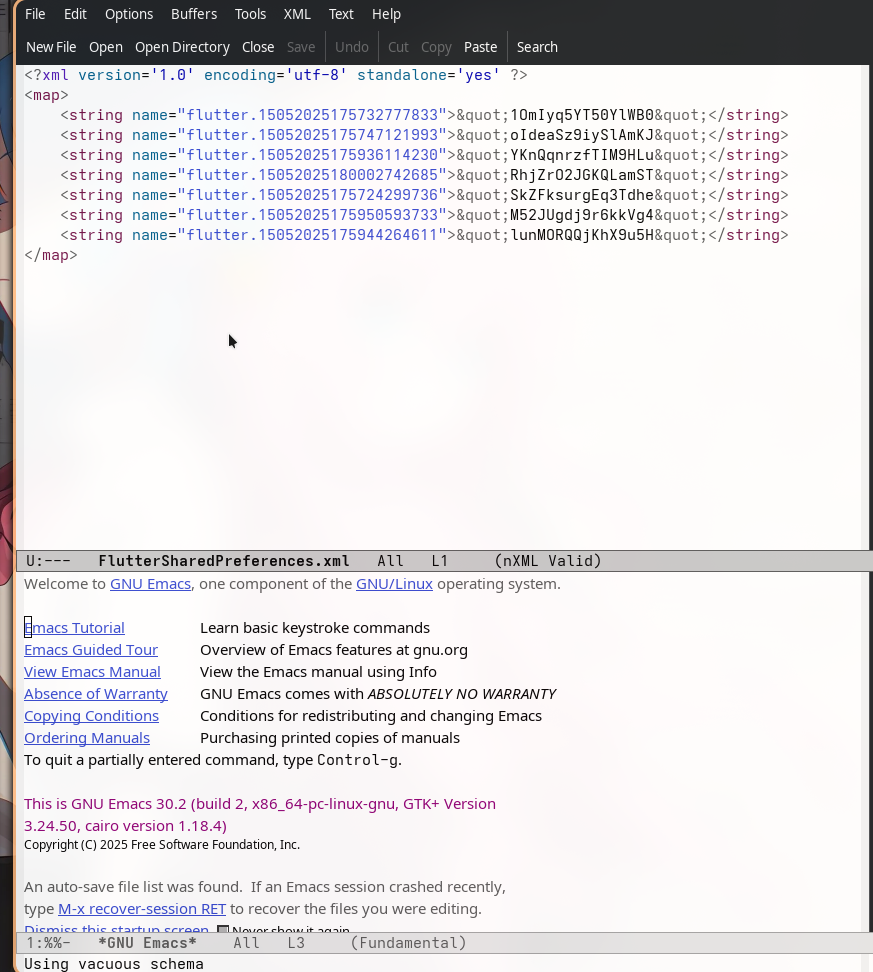

The challenge focused on recovering notes. During the search for notes files, one file was found with a base64-encoded name:

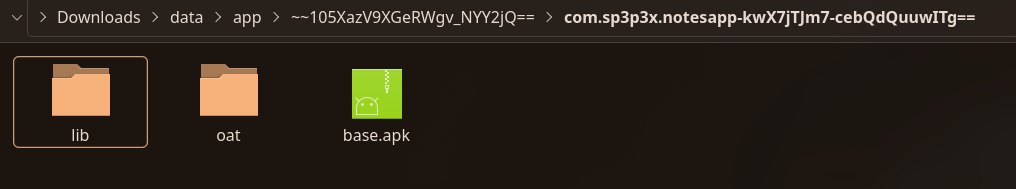

This directory contained the following files:

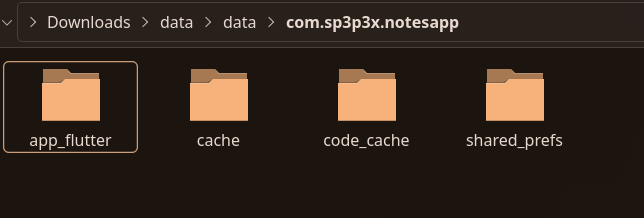

Flutter App Analysis

Further exploration revealed this was about recovering data from a Flutter app:

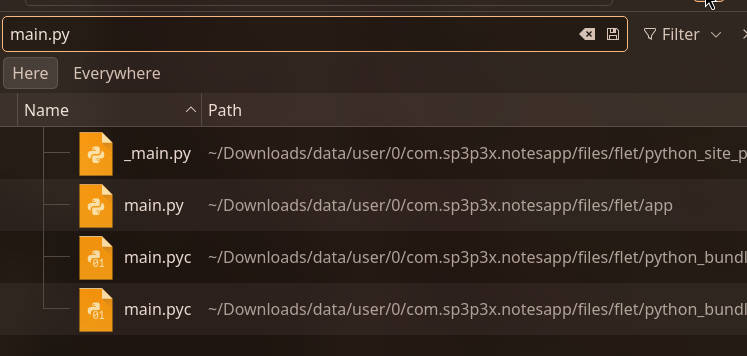

Source Code Discovery

Since Flutter uses Python (via Flet framework), i searched for Python files containing the APK logic. The main application file was found:

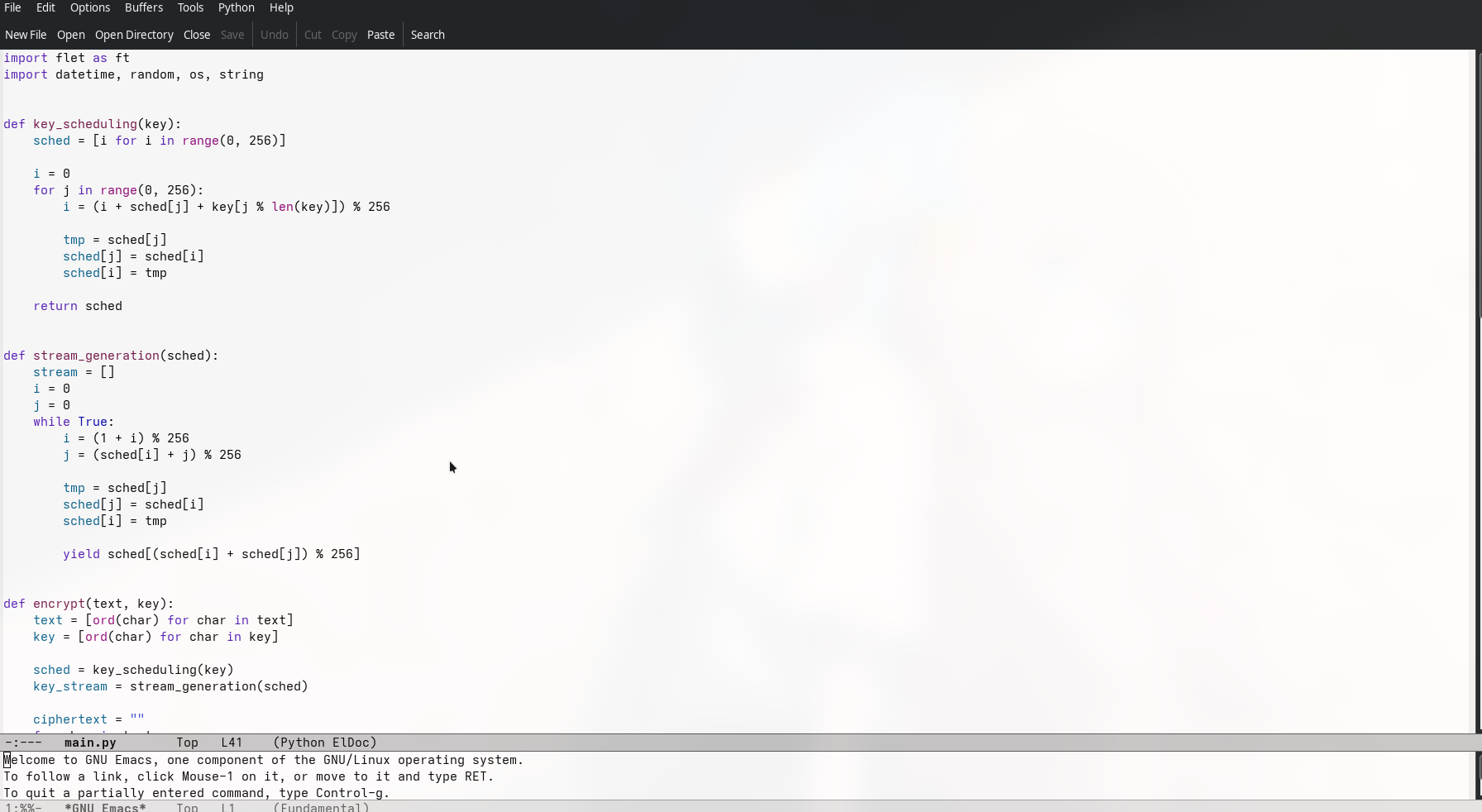

Encryption Implementation

The discovered Python code revealed the notes app’s encryption scheme:

import flet as ft

import datetime, random, os, string

def key_scheduling(key):

sched = [i for i in range(0, 256)]

i = 0

for j in range(0, 256):

i = (i + sched[j] + key[j % len(key)]) % 256

tmp = sched[j]

sched[j] = sched[i]

sched[i] = tmp

return sched

def stream_generation(sched):

stream = []

i = 0

j = 0

while True:

i = (1 + i) % 256

j = (sched[i] + j) % 256

tmp = sched[j]

sched[j] = sched[i]

sched[i] = tmp

yield sched[(sched[i] + sched[j]) % 256]

def encrypt(text, key):

text = [ord(char) for char in text]

key = [ord(char) for char in key]

sched = key_scheduling(key)

key_stream = stream_generation(sched)

ciphertext = ""

for char in text:

enc = str(hex(char ^ next(key_stream))).lower()

ciphertext += enc

return ciphertext

def storeData(page, content):

app_data_path = os.getenv("FLET_APP_STORAGE_DATA")

fileName = f"{datetime.datetime.now().strftime("%d%m%Y%H%M%S%f")}"

my_file_path = os.path.join(app_data_path, fileName)

key = "".join(

random.choice(string.ascii_letters + string.digits) for _ in range(16)

)

encText = encrypt(content, key)

page.client_storage.set(fileName, key)

with open(my_file_path, "w") as f:

f.write(encText)

page.open(ft.SnackBar(ft.Text(f"File saved to App Data Storage!")))

def main(page: ft.Page):

def saveNote(e):

data = inputBox.value

if data != "":

storeData(page, data)

else:

page.open(ft.SnackBar(ft.Text("Empty content!")))

appBar = ft.AppBar(title=ft.Text("Notes App"))

inputBox = ft.TextField(hint_text="Enter some text...", multiline=True, min_lines=3)

page.appbar = appBar

page.add(inputBox)

page.add(

ft.ElevatedButton(text="Save Note", on_click=saveNote, style=ft.ButtonStyle())

)

ft.app(main)The application allows users to create and save encrypted notes with the following workflow: When a user enters text and clicks “Save Note”, the application generates a unique filename based on the current timestamp (format: DDMMYYYYHHMMSSμs). It then creates a random 16-character encryption key consisting of letters and digits. The note content is encrypted using a custom implementation of the RC4 stream cipher algorithm, which involves two main phases: key scheduling (which initializes a 256-byte state array based on the encryption key) and stream generation (which produces a pseudo-random keystream). The encryption process XORs each character of the plaintext with the corresponding keystream byte and converts the result to hexadecimal format. The encrypted text is stored in a file within the app’s data directory, while the encryption key is separately stored in the client storage using the filename as the identifier. This design means that to decrypt any saved note, you need both the encrypted file and its corresponding encryption key from the client storage, making the encryption key essential for data recovery.

so I wrote a Python script that:

- Implemented the RC4 decryption algorithm (mirroring the encryption code)

- Parsed the hex-encoded ciphertext

- XORed each byte with the keystream to recover plaintext

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""Simple decryption script for the notes challenge"""

import os

def key_scheduling(key):

sched = [i for i in range(0, 256)]

i = 0

for j in range(0, 256):

i = (i + sched[j] + key[j % len(key)]) % 256

tmp = sched[j]

sched[j] = sched[i]

sched[i] = tmp

return sched

def stream_generation(sched):

i = 0

j = 0

while True:

i = (1 + i) % 256

j = (sched[i] + j) % 256

tmp = sched[j]

sched[j] = sched[i]

sched[i] = tmp

yield sched[(sched[i] + sched[j]) % 256]

def decrypt(ciphertext, key):

key = [ord(char) for char in key]

sched = key_scheduling(key)

key_stream = stream_generation(sched)

# Parse hex values from format: 0xXX0xYY0xZZ...

hex_values = []

i = 0

while i < len(ciphertext):

if ciphertext[i:i+2] == '0x':

j = i + 2

while j < len(ciphertext) and ciphertext[j:j+2] != '0x':

j += 1

hex_val = ciphertext[i:j]

hex_values.append(int(hex_val, 16))

i = j

else:

i += 1

plaintext = ""

for encrypted_byte in hex_values:

decrypted_byte = encrypted_byte ^ next(key_stream)

plaintext += chr(decrypted_byte)

return plaintext

# Keys from client storage

KEYS = {

"15052025175732777833": "1OmIyq5YT50YlWB0",

"15052025175747121993": "oIdeaSz9iySlAmKJ",

"15052025175936114230": "YKnQqnrzfTIM9HLu",

"15052025180002742685": "RhjZrO2JGKQLamST",

"15052025175724299736": "SkZFksurgEq3Tdhe",

"15052025175950593733": "M52JUgdj9r6kkVg4",

"15052025175944264611": "lunMORQQjKhX9u5H",

}

print("\n" + "="*70)

print("DECRYPTING ALL NOTES")

print("="*70 + "\n")

for filename, key in KEYS.items():

if os.path.exists(filename):

print(f"\n{'='*70}")

print(f"File: {filename}")

print(f"Key: {key}")

print(f"{'='*70}")

with open(filename, 'r') as f:

ciphertext = f.read()

try:

plaintext = decrypt(ciphertext, key)

print(f"Decrypted content:\n{plaintext}")

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error decrypting: {e}")

print(f"{'='*70}\n")

else:

print(f"File not found: {filename}")

print("\n✓ Decryption complete!\n")15052025175732777833: "well this was easy"

15052025175747121993: "i'll give you the first part of the flag :)"

15052025175936114230: "first part of the flag: w311_7h47_p4r7_w45_345y"

15052025180002742685: "f4k3_f14g"

15052025175724299736: "hello there"

15052025175950593733: "boop"

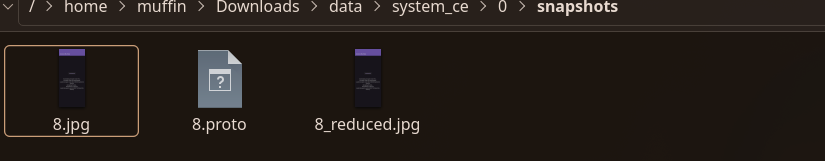

15052025175944264611: "hehehe"After an hour of going through all the files i found this snapshots folder ( i tried organising the files by images , txt , png etc and came across this title 0

After analyzing the Android filesystem dump, we identified two key applications in the /data/app/ directory:

com.sp3p3x.notesapp- A notes application (already analyzed for flagPart1)com.example.accessmydata- The target application for flagPart2

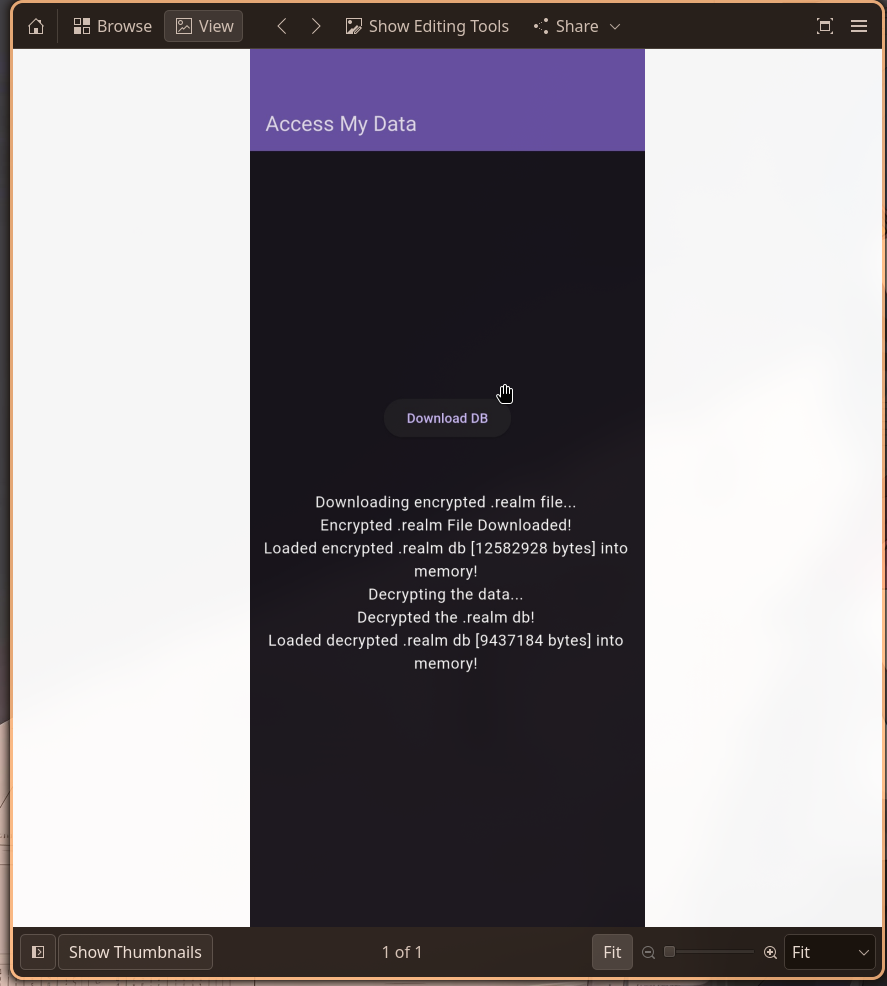

The challenge description hinted at finding deleted data from a “realm db”, and a screenshot found in /data/system_ce/0/snapshots/ confirmed the existence of an app that downloads and decrypts a realm file

The Access My Data APK was found at:

/data/app/~~hvxKjg-YJ69UXXtnoCmWcw==/com.example.accessmydata-rkCVbU6Yb-jHyAaRmU8b0Q==/base.apkTerminal output:

$ find /data/app -name "*accessmydata*" -name "*.apk"

/data/app/~~hvxKjg-YJ69UXXtnoCmWcw==/com.example.accessmydata-rkCVbU6Yb-jHyAaRmU8b0Q==/base.apk

$ ls -lh base.apk

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 21M May 15 2025 base.apkFlutter applications are unique in the Android ecosystem because they don’t use traditional Java/Kotlin code. Instead, they compile Dart code to native machine code using Ahead-Of-Time (AOT) compilation. This results in two important native libraries:

- libflutter.so - The Flutter engine (shared across all Flutter apps)

- libapp.so - The application-specific code compiled from Dart

The Dart code is embedded within libapp.so as a snapshot, which contains:

- Compiled Dart VM bytecode

- AOT-compiled native code

- An Object Pool with string literals and constants

- Type information and metadata

This compilation method makes traditional APK analysis tools (like jadx or dex2jar) useless, as there’s no DEX bytecode to decompile:(

We extracted the APK to access the native libraries:

$ mkdir apk_extracted

$ unzip -q base.apk -d apk_extracted/

$ ls -lh apk_extracted/lib/arm64-v8a/

total 16M

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 4.7M Jan 1 1981 libapp.so

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 11M Jan 1 1981 libflutter.soThe libapp.so file (4.7 MB) contains all the application logic we need to reverse engineer.

Blutter, a portmanteau of “B(l)utter” that plays on both buttering and Flutter, is a reverse engineering tool built specifically with Flutter applications in mind. Unlike traditional disassemblers that treat Flutter binaries as opaque native code, Blutter understands the internal structure of the Dart VM snapshot embedded inside libapp.so. It is able to parse this snapshot, extract the object pool that contains constants, strings, and type information, and use that data to reconstruct readable pseudo-Dart code complete with symbols and function names. In addition to this higher-level reconstruction, Blutter can also generate annotated assembly listings that bridge the gap between low-level instructions and Dart-level logic, and even produce Frida scripts to assist with dynamic analysis and runtime instrumentation.

When we run Blutter, it performs several automated steps:

$ python3 blutter.py /path/to/apk_extracted/lib/arm64-v8a /path/to/blutter_outputDuring execution, Blutter follows a fairly involved but systematic process to adapt itself to the exact Flutter application being analyzed. It begins by inspecting libflutter.so to determine the precise Dart SDK version used when the app was compiled. This step is essential, as the internal layout of Dart VM snapshots varies between versions, and using the wrong format would make accurate parsing impossible. In this case, Blutter identifies the app as being built with Dart 3.7.2, along with the associated snapshot hash, target architecture, and compilation flags, all of which guide the rest of the analysis.

If a matching analysis backend for that Dart version is not already available, Blutter automatically prepares one. It fetches the Dart SDK source from the official repository, checks out the exact version tag, and compiles the Dart VM runtime into a static library tailored to the target architecture. Blutter then rebuilds its own analysis components against this library, a process that can take several minutes and produces verbose build output as each part of the VM is compiled and linked.

Once the environment is ready, Blutter moves on to snapshot analysis. It parses libapp.so to locate the embedded Dart VM snapshot, extracts the object pool containing constants and string literals, reconstructs the application’s class hierarchy, and identifies function entry points to recover the overall code structure. Using this information, Blutter generates its final artifacts, producing annotated assembly listings, reconstructed function and class definitions, inline constants, and a mapped control flow for each Dart library. At the end of the process, it also generates a Frida script, enabling dynamic instrumentation of the recovered logic during runtime analysis.

Examining the Output Structure

$ ls -la blutter_output/

total 1524

drwxr-xr-x 1 muffin muffin 86 Dec 30 18:56 .

drwxr-x--x 1 muffin muffin 894 Dec 30 18:56 ..

drwxr-xr-x 1 muffin muffin 478 Dec 30 18:56 asm/ # Assembly listings

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 221632 Dec 30 18:56 blutter_frida.js # Frida script template

drwxr-xr-x 1 muffin muffin 56 Dec 30 18:56 ida_script/ # IDA Pro integration

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 376330 Dec 30 18:56 objs.txt # Nested object dump

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 957372 Dec 30 18:56 pp.txt # Complete Object Pool

$ ls blutter_output/asm/ | head -10

accessmydata/

async/

characters/

collection/

.dart_tool/

dio/

encrypt/

flutter/

...The asm/ directory contains subdirectories for each Dart package used in the app. Our target is accessmydata/main.dart.

Locating the Main Application Code

$ ls -lh blutter_output/asm/accessmydata/

total 52

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 51467 Dec 30 18:56 main.dartThe main.dart file contains 51 KB of annotated assembly code representing the application’s core logic.

Blutter generates assembly listings that interleave ARM64 assembly with Dart-level semantic comments. Here’s an example of the format:

_ _decryptData(/* No info */) {

// addr: 0x2db4c0, size: 0x174

// 0x2db4c0: EnterFrame

0x2db4c0: stp fp, lr, [SP, #-0x10]!

0x2db4c4: mov fp, SP

// 0x2db4c8: AllocStack(0x30)

0x2db4c8: sub SP, SP, #0x30Explanation:

- Function signature:

_ _decryptData(/* No info */)- Dart function name - Address and size: addr: 0x2db4c0, size: 0x174 (372 bytes)

- Comments:

// 0x2db4c0: EnterFrame- high-level operation - Assembly:

0x2db4c0: stp fp, lr, [SP, #-0x10]!- actual ARM64 instruction - PP references:

[PP, #0x90]- references to the Object Pool

Extracting the Encryption Keys

the download URL:

// 0x304ed8: r16 = "https://github.com/chicken-jockeyy/confidentialdb/raw/refs/heads/main/enc.bin"

// 0x304ed8: add x16, PP, #0xd, lsl #12 ; [pp+0xd348] "https://github..."

/ 0x304edc: ldr x16, [x16, #0x348]These literal strings are stored in the Object Pool (PP) and loaded into registers for use.

// Load key part 1 into x16

// 0x2db4f8: r16 = "04e0d32be85f3b42"

// 0x2db4f8: add x16, PP, #0xb, lsl #12

/ 0x2db4fc: ldr x16, [x16, #0x5a0]

// Load key part 2 into x30 (lr)

// 0x2db500: r30 = "7173047a9d6574e5"

// 0x2db500: add lr, PP, #0xb, lsl #12

/ 0x2db504: ldr lr, [lr, #0x5a8]

// Push both parts onto stack

// 0x2db508: stp lr, x16, [SP]

// 0x2db50c: r0 = +()

// Concatenate the two strings: "04e0d32be85f3b427173047a9d6574e5"Then the code creates a reversed iterable:

// 0x2db540: r0 = ReversedListIterable()

// 0x2db540: bl #0x2bee38 ; AllocateReversedListIterableStub

// 0x2db558: r0 = join()

// 0x2db558: bl #0x28e4f8 ; [dart:_internal] ListIterable::joinThis reverses the concatenated key string character by character:

- Original:

04e0d32be85f3b427173047a9d6574e5 - Reversed:

5e4756d9a740371724b3f58eb23d0e40

// 0x2db564: r0 = Key()

// Create an encryption key object

// 0x2db578: r0 = AES()

// 0x2db578: bl #0x304864 ; AllocateAESStub -> AES

// 0x2db588: r0 = AES()

// 0x2db588: bl #0x2db870 ; [package:encrypt/encrypt.dart] AES::AES

// Initialize AES cipher with the reversed keyTo find which AES mode is used, we examined the Object Pool dump:

$ grep -i "ecb\|AESMode" blutter_output/pp.txt

[pp+0xb5d8] Obj!AESMode@5032b1 : {

off_10: "ecb"

}

[pp+0xb5f0] Map<AESMode, String>(8) {

Obj!AESMode@503291: "CBC",

Obj!AESMode@503271: "CFB-64",

Obj!AESMode@503251: "CTR",

Obj!AESMode@5032b1: "ECB",

Obj!AESMode@503231: "OFB-64/GCTR",

Obj!AESMode@503211: "OFB-64",

...

}Cross-referencing with the assembly:

// 0x2db880: r4 = Instance_AESMode

// 0x2db880: add x4, PP, #0xb, lsl #12 ; [pp+0xb5d8] Obj!AESMode@5032b1

/ 0x2db884: ldr x4, [x4, #0x5d8]The constant at pp+0xb5d8 is Obj!AESMode@5032b1, which corresponds to “ECB” mode in the enum map.

Step 4: Decryption and Base64 Decode

// 0x2db5b8: r0 = decrypt()

// 0x2db5b8: bl #0x2db6a0 ; [package:encrypt/encrypt.dart] Encrypter::decrypt

// Decrypt the encrypted data using AES-ECB

// 0x2db5c0: r0 = base64Decode()

// 0x2db5c0: bl #0x2db634 ; [dart:convert] ::base64Decode

// Decode the decrypted Base64 string to binary-

Key Preparation:

key_part1 = "04e0d32be85f3b42" key_part2 = "7173047a9d6574e5" combined = "04e0d32be85f3b427173047a9d6574e5" (32 characters) reversed = "5e4756d9a740371724b3f58eb23d0e40" (32 characters → 16 bytes UTF-8) -

Download encrypted file:

URL: https://github.com/chicken-jockeyy/confidentialdb/raw/refs/heads/main/enc.bin Size: 12,582,928 bytes -

AES-ECB Decryption:

Cipher: AES-128 (128-bit key = 16 bytes) Mode: ECB (Electronic Codebook) Key: "5e4756d9a7403717" + "24b3f58eb23d0e40" (16 ASCII characters) Input: enc.bin (raw binary data) Output: Base64-encoded string -

Base64 Decoding:

Input: Base64 string (from AES decryption) Output: decrypted.realm (9,437,184 bytes)

Part 6: Implementing the Decryptor

Downloading the Encrypted File

$ curl -L -o enc.bin "https://github.com/chicken-jockeyy/confidentialdb/raw/refs/heads/main/enc.bin"

% Total % Received % Xferd Average Speed Time Time Time Current

Dload Upload Total Spent Left Speed

100 12288k 100 12288k 0 0 1988k 0 0:00:06 0:00:06 --:--:-- 3087k

$ ls -lh enc.bin

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 13M Dec 30 18:50 enc.bin

$ file enc.bin

enc.bin: dataThe file is 12 MB of raw binary data (AES-encrypted).

Creating Cargo.toml for Rust Dependencies

[package]

name = "decrypt_realm"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2021"

[dependencies]

aes = "0.8"

base64 = "0.21"Required crates:

- aes: Provides AES block cipher implementation

- base64: Handles Base64 encoding/decoding

Running the Rust Decryptor

$ cargo run --release

Compiling aes v0.8.3

Compiling base64 v0.21.5

Compiling decrypt_realm v0.1.0

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 3.42s

Running `target/release/decrypt_realm`

Key part 1: 04e0d32be85f3b42

Key part 2: 7173047a9d6574e5

Combined key: 04e0d32be85f3b427173047a9d6574e5

Reversed key: 5e4756d9a740371724b3f58eb23d0e40

Encrypted data size: 12582928 bytes

AES ECB decryption complete

Base64 decoding complete

Realm database saved as 'decrypted.realm'

File size: 9437184 bytes (9 MB)

File appears to be a valid Realm database

Verifying the Decrypted File

$ ls -lh decrypted.realm

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 9.0M Dec 30 19:15 decrypted.realm

$ file decrypted.realm

decrypted.realm: data

$ hexdump -C decrypted.realm | head -20

00000000 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

00000020 54 4c 44 42 00 00 00 00 0f 72 65 61 6c 6d 5f 76 |TLDB.....realm_v|

00000030 65 72 73 69 6f 6e 00 00 14 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 |ersion..........|Why the Key is Reversed

Looking at the Dart code pattern:

String keyPart1 = "04e0d32be85f3b42";

String keyPart2 = "7173047a9d6574e5";

String combined = keyPart1 + keyPart2;

String reversed = combined.split('').reversed.join('');This reversal serves multiple purposes:

- Obfuscation: Makes static analysis slightly harder

- Key Derivation: Creates a “derived” key from hardcoded parts

- String Manipulation: Common pattern in Dart for simple transformations

The reversed key 5e4756d9a740371724b3f58eb23d0e40 is exactly 32 ASCII characters, which when encoded as UTF-8 bytes gives us the required 16-byte (128-bit) AES key.

With our Python decryption script complete, we can now decrypt the realm database:

$ python3 decrypt_realm.py

Realm database saved as 'decrypted.realm'

File size: 9437184 bytesVerification of the decrypted file:

$ ls -lh decrypted.realm

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 9.0M Dec 30 19:21 decrypted.realm

$ file decrypted.realm

decrypted.realm: data

$ hexdump -C decrypted.realm | head -10

00000000 78 96 88 00 00 00 00 00 c8 36 88 00 00 00 00 00 |x........6......|

00000010 54 2d 44 42 09 09 00 00 41 41 41 41 0e 00 00 05 |T-DB....AAAA....|

00000020 70 6b 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |pk..............|

00000030 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 1d |................|

00000040 6d 65 74 61 64 61 74 61 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |metadata........|

00000050 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 17 |................|

00000060 63 6c 61 73 73 5f 52 65 61 6c 6d 54 65 73 74 43 |class_RealmTestC|

00000070 6c 61 73 73 30 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 0a |lass0...........|

00000080 63 6c 61 73 73 5f 52 65 61 6c 6d 54 65 73 74 43 |class_RealmTestC|

00000090 6c 61 73 73 31 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 0a |lass1...........|Key observations from the hex dump:

- Bytes 0x10-0x13:

54 2d 44 42= “T-DB” - Realm database magic header - Bytes 0x14-0x17:

41 41 41 41= “AAAA” - Region marker for unused/free space - Offset 0x40: “metadata” string - Database metadata section

- Offset 0x60: “class_RealmTestClass0” - First database schema class

- Offset 0x80: “class_RealmTestClass1” - Second database schema class

Before we can recover deleted data, we need to understand how Realm databases work:

Realm Database Architecture

Realm is a mobile-first database designed for iOS and Android applications. Unlike SQLite which uses SQL and table-based storage, Realm uses:

- Object-based Model: Data is stored as objects, not rows and columns

- Binary Format: Uses a custom binary format (not SQL)

- MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control): Maintains multiple versions of data

- Zero-Copy Architecture: Data is memory-mapped directly from disk

Why Deleted Data Persists

Realm uses MVCC, which means when you “delete” data, it doesn’t immediately erase it. Instead:

- The data is marked as deleted/unused

- A new version of the database state is created

- The old version’s data remains in unused space

- Garbage collection happens later (if at all)

This creates a forensic opportunity: deleted records often remain in unused regions of the database file.

To recover deleted data from the Realm database, we use realm_recover, a specialized forensics tool designed specifically for analyzing Realm files. While exploring this approach, I came across prior research that discusses how deleted records in mobile application databases are often not immediately erased from disk. Instead, remnants of these records can persist within the database structure, making recovery possible through careful analysis. This idea is reinforced by both academic work and practical discussions from the developer and forensics communities, which describe how Realm’s internal storage format can retain deleted objects long enough for them to be reconstructed. These techniques are commonly applied in Android forensics, where understanding the database layout allows investigators to extract historical or deleted application data that would otherwise appear lost.

References

-

Smart Techniques to Extract the Deleted Data From the Android Application https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2666281722000221

-

Stack Overflow discussion on restoring deleted Realm objects https://stackoverflow.com/questions/52384845/how-to-restore-an-item-deleted-from-realm

-

Smart Techniques to Extract the Deleted Data From the Android Application (Academia.edu) https://www.academia.edu/77798036/Smart_Techniques_to_Extract_the_Deleted_Data_Form_the_Android_Application

$ cd /tmp

$ git clone https://github.com/hyuunnn/realm_recover.git

Cloning into 'realm_recover'...

remote: Enumerating objects: 84, done.

remote: Total 84 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 84

Receiving objects: 100% (84/84), 27.13 KiB | 1.51 MiB/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (42/42), done.

$ ls /tmp/realm_recover/

LICENSE objects.py README.md realm_recover.py sample util.pyThe tool consists of several components:

- realm_recover.py: Main recovery script

- objects.py: Realm object parsing logic

- util.py: Utility functions for binary analysis

- sample/: Sample realm database for testing

Running the Realm Recovery Tool

Execute the recovery tool on our decrypted realm database:

$ python3 /tmp/realm_recover/realm_recover.py --file decrypted.realm

[Tool runs silently, generating output files]The tool doesn’t produce console output but generates several analysis files:

$ ls -lh *.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 1705 Dec 30 19:23 compare_objects.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 1033382 Dec 30 19:23 data_storages.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 1798075 Dec 30 19:23 scan_all_objects.txt

-rw-r--r-- 1 muffin muffin 1117764 Dec 30 19:23 scan_unused_objects.txtUnderstanding the Output Files

-

scan_all_objects.txt (1.8 MB):

- Every object found in the database

- Includes both active and deleted objects

- Organized by offset and type

-

scan_unused_objects.txt (1.1 MB):

- Objects not referenced by active tree roots

- These are deleted/orphaned objects

- Primary target for forensic recovery

-

data_storages.txt (1.0 MB):

- Raw data storage analysis

- Binary dumps of storage regions

-

compare_objects.txt (1.7 KB):

- Comparison of TreeRootOffset01 vs TreeRootOffset02

- Shows what changed between versions

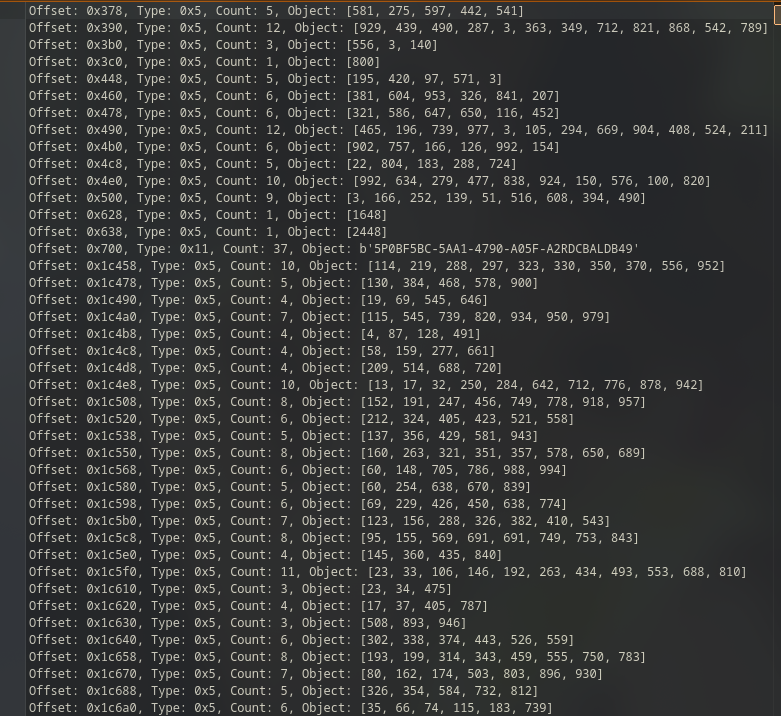

The challenge description states the flag is in a “string which was modified and then deleted from the realm db”. This means we need to search scan_unused_objects.txt.

Search for UUID-pattern strings (the typical format for test data in Realm databases):

$ grep -E "[0-9A-F]{8}-[0-9A-Z]{4}-[0-9A-Z]{4}-[0-9A-Z]{4}-[0-9A-Z]{12}" scan_unused_objects.txtThis grep pattern searches for:

[0-9A-F]{8}: 8 hex digits-: Literal hyphen[0-9A-Z]{4}: 4 alphanumeric characters (allowing non-hex)- Pattern repeats:

8-4-4-4-12(UUID format)

Result (truncated for clarity):

Offset: 0x800000, Type: 0x11, Count: 534043, Object: [

...

b'$97990266-4B4D-4306-A1EB-0FA8B4025844\x06\x04\x02',

b'$48E1F6A5-C826-4244-B1CF-008E451606F3\r\x01\x01\x01',

...

b'$5P0BF5BC-5AA1-4790-A05F-A2RDCBALDB49\x06\x04\x02\x03',

...

]

Among hundreds of valid UUIDs, one stands out:

5P0BF5BC-5AA1-4790-A05F-A2RDCBALDB49This is flagPart2.

The realm_recover tool is able to successfully retrieve deleted data because of how Realm manages its internal storage and object lifecycle. Realm relies on a Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC) model, which means older versions of objects are preserved for consistency and concurrency purposes instead of being immediately removed. As a result, when an object is deleted, its previous version can still remain in memory or on disk for some time.

In addition to this, realm_recover scans regions of the database file that are no longer actively allocated, allowing it to identify data that is not referenced by the current database state but has not yet been overwritten. Because the tool understands Realm’s binary object layout, it can correctly parse these leftover structures and reconstruct meaningful records from raw bytes. In this case, the deleted UUID was found at offset 0x800000 within a region marked as unused. Although the object was no longer linked from the active database tree, its binary representation was still fully intact in the file, and the absence of garbage collection or overwrite made recovery possible.

Complete Flag:

bi0sctf{w311_7h47_p4r7_w45_345y_5P0BF5BC-5AA1-4790-A05F-A2RDCBALDB49}