32 Rounds of TEA and Psychological Damage, Surviving a Stripped 32-bit Binary

← back to blog

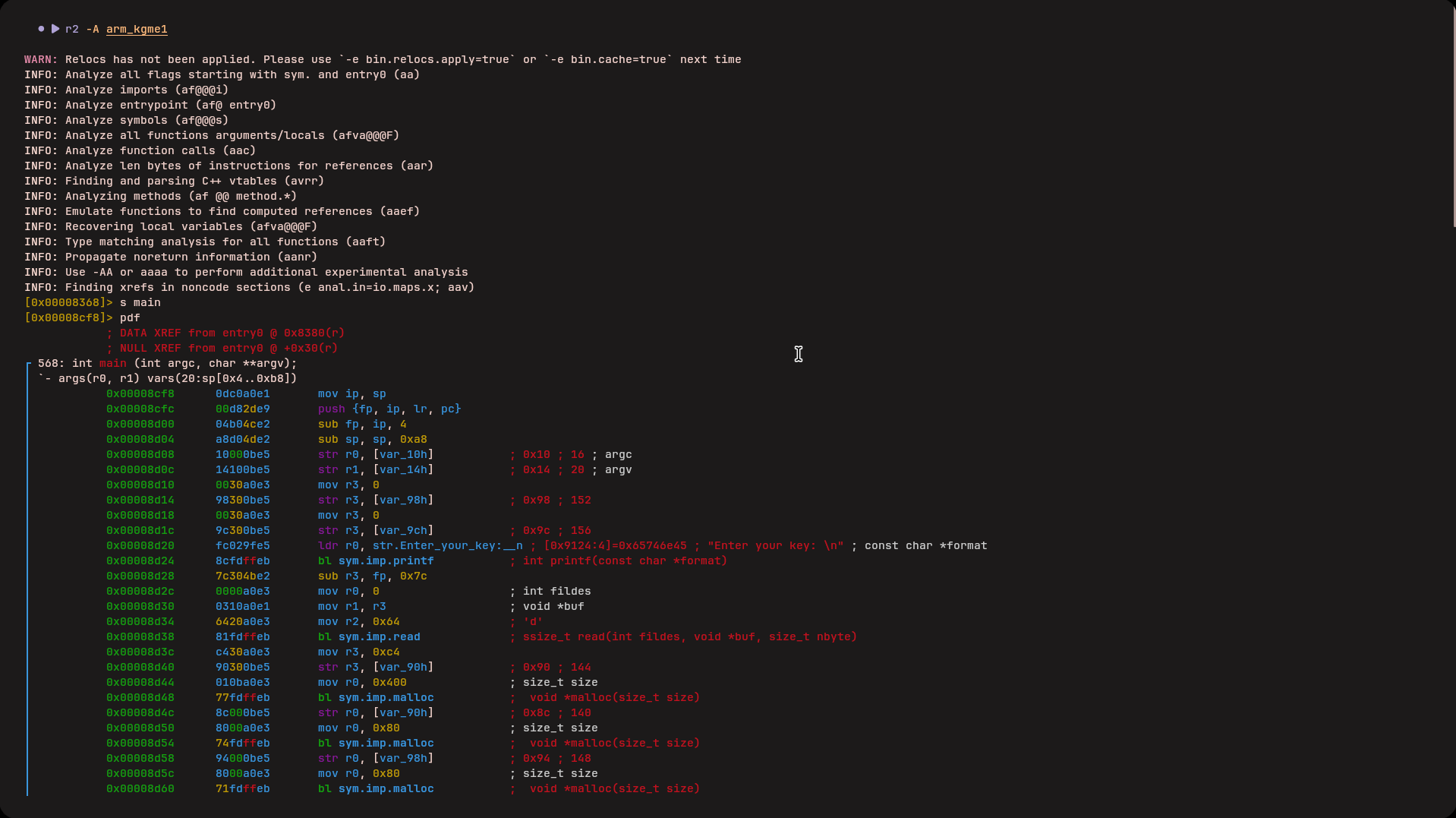

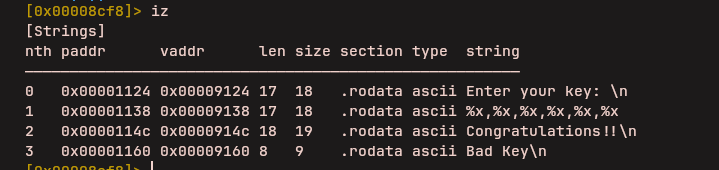

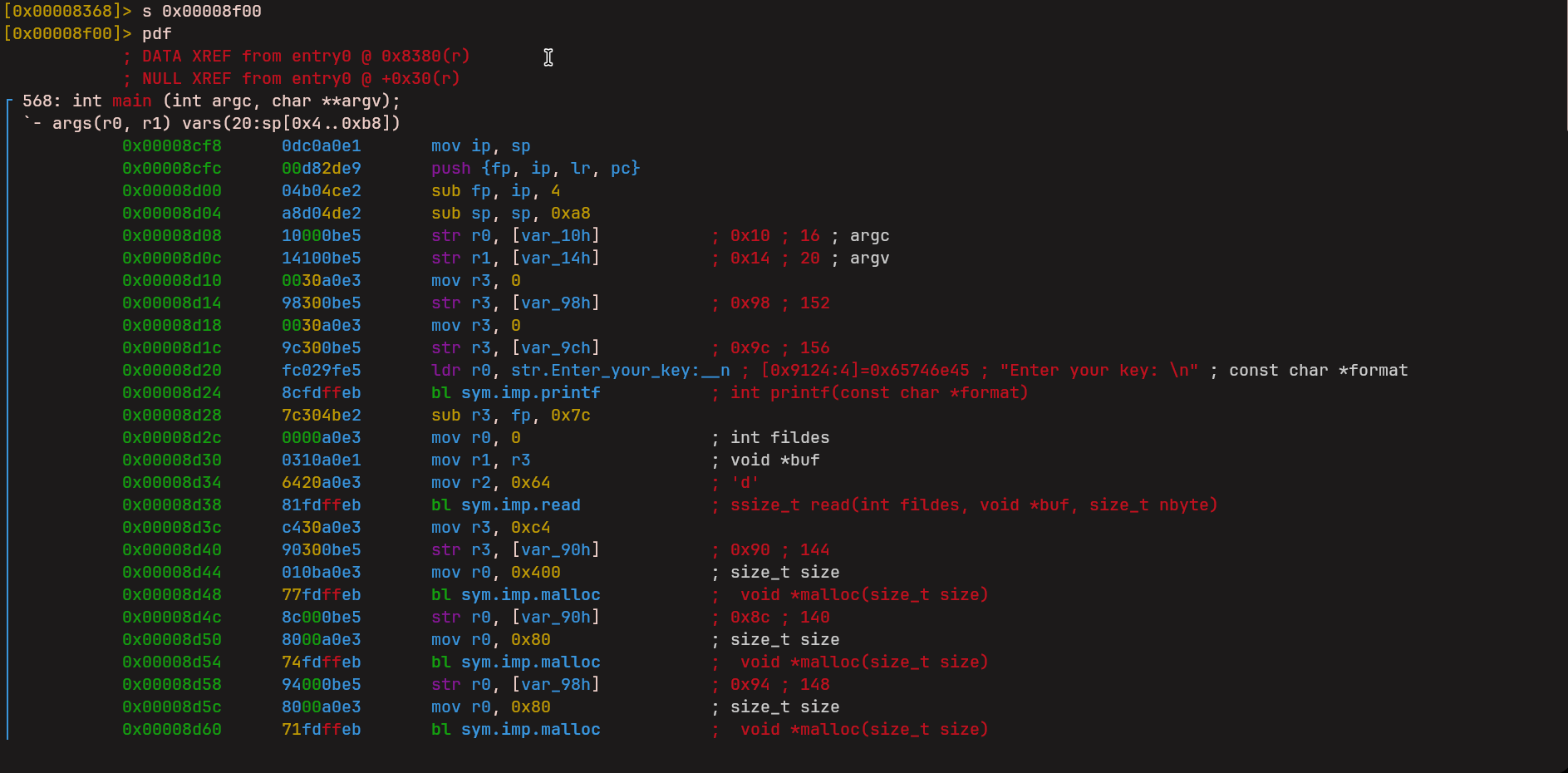

This program is a 32-bit ARM binary. This means it is meant to run on ARM systems and not on regular x86 machines, so it cannot be run directly. The binary is also stripped, meaning there are no useful function names, and it is dynamically linked. Even though it cannot be executed easily, running it is not required. Static analysis is enough to understand the logic and solve the challenge.

Initial Analysis

When the program starts, it prints a message and waits for user input. The input is read using the read() function. Instead of keeping the input as raw text, the program parses it into numbers and stores them contiguously in a heap-allocated buffer. These parsed values are later treated as fake registers for a custom virtual machine implemented by the binary.

The Virtual Machine

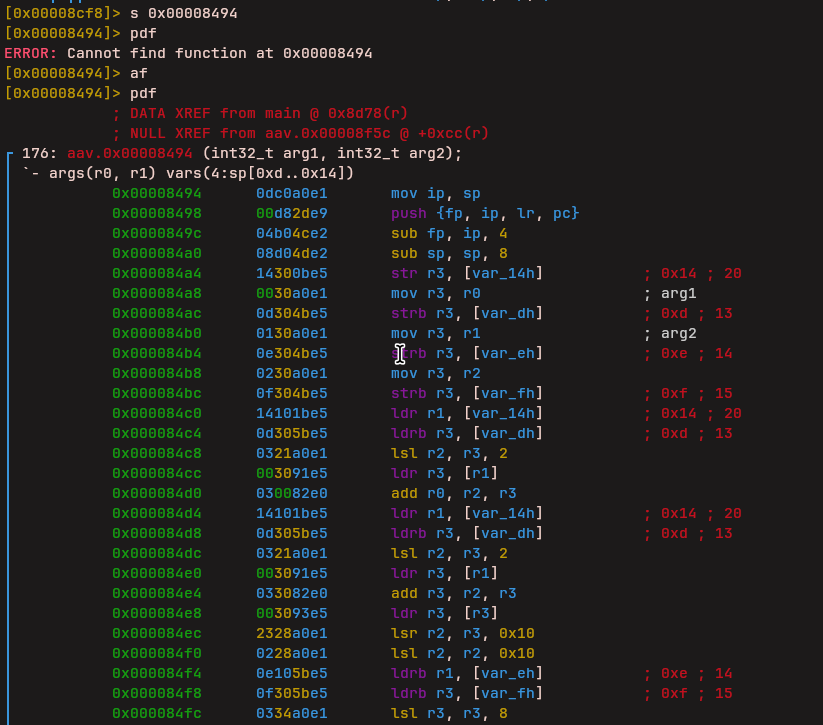

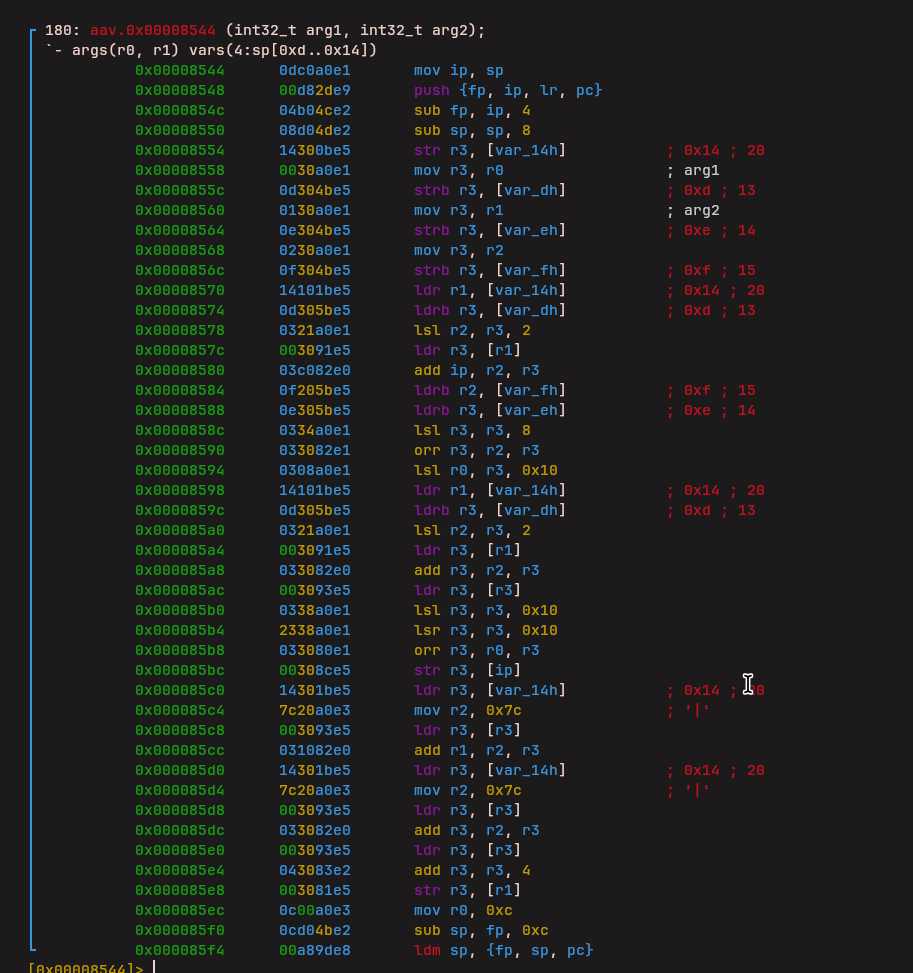

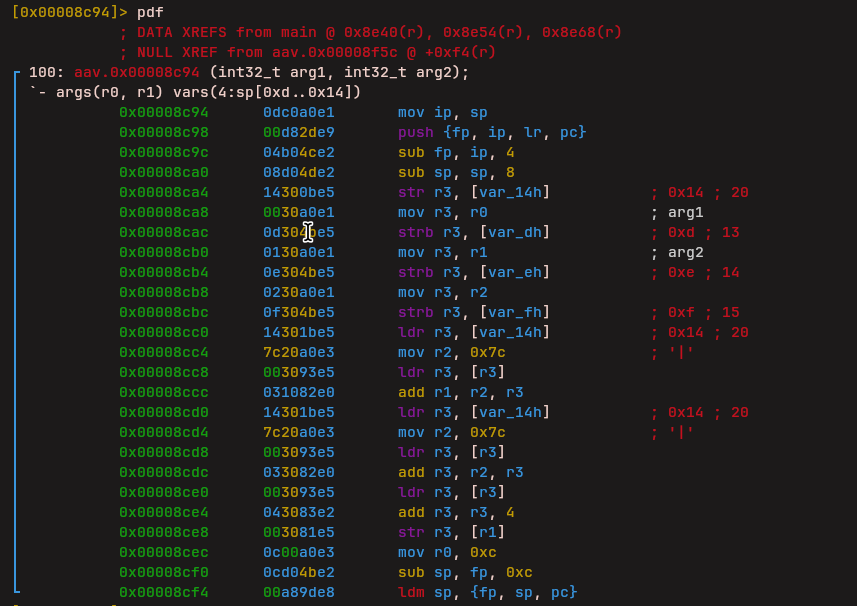

After parsing the input, execution jumps into a function named fcn.00008410. This function works as the main VM interpreter. From this point onward, the program is no longer executing normal ARM instructions. Instead, it starts reading and executing VM bytecode stored as data inside the binary.

Each VM instruction is 4 bytes long. The first byte is the opcode, which decides what operation to perform. The remaining three bytes are arguments. The opcode is used as an index into a jump table, which then jumps to the corresponding instruction handler.

The VM maintains its own execution state similar to a real CPU. It has its own registers, its own stack, and its own instruction pointer. Register index 30 is used as the stack pointer, while register index 31 stores the current VM instruction pointer.

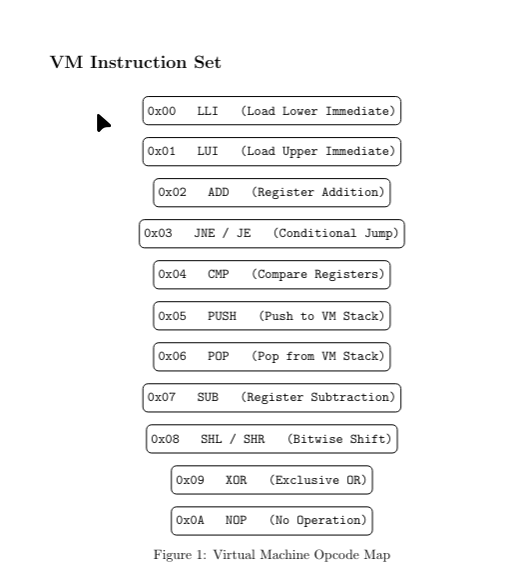

Reverse Engineering the Instruction Set

By analyzing where the jump table leads and observing what each handler does, the VM instruction set can be identified. As the purpose of each handler becomes clear, they are renamed in radare2 to match their behavior. For example, one instruction was identified as a load lower immediate and renamed LLi.

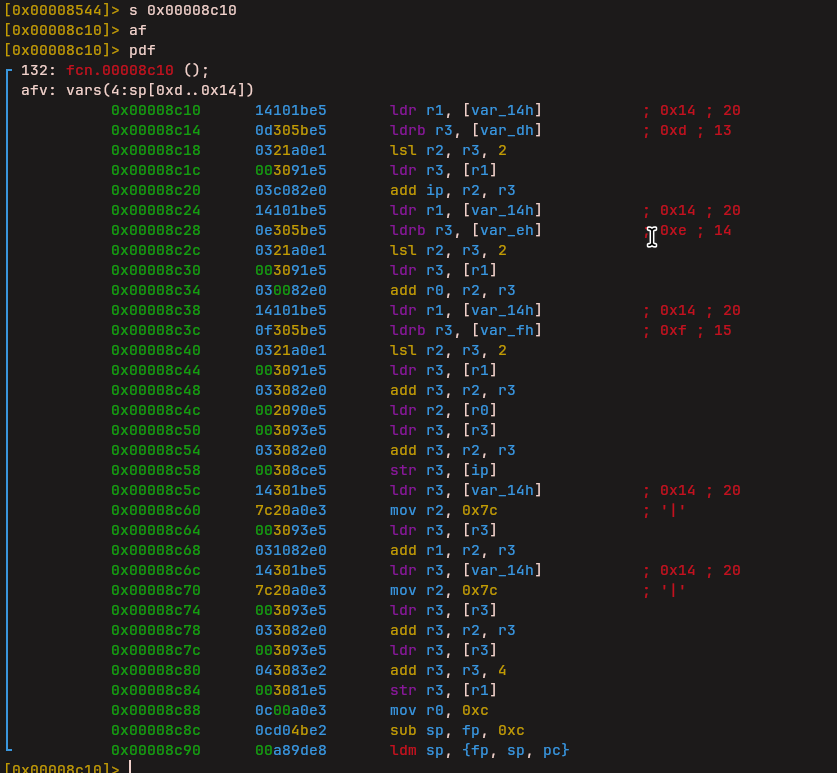

Load Lower Immediate (LLi)

This instruction loads an immediate value into the lower portion of a register.

Load Upper Immediate (LUi)

Another similar instruction was identified as Load Upper Immediate, which loads an immediate value into the upper portion of a register.

Addition (vm_add)

The next instruction handled addition between values.

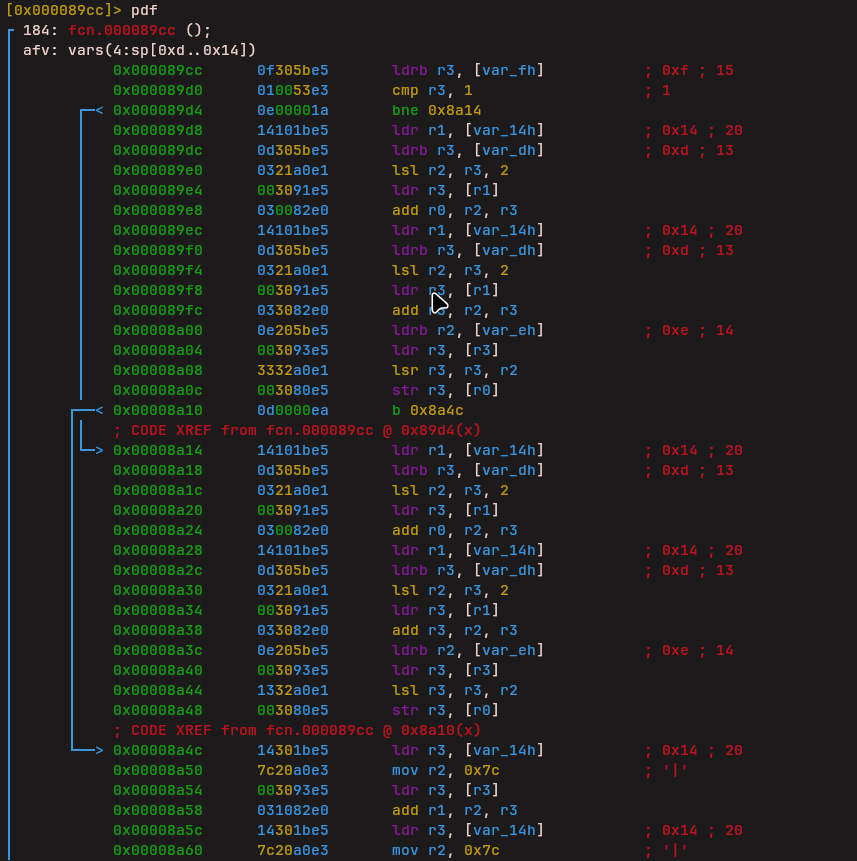

Conditional Jump

The next instruction was particularly complex. It combines two bytes into a 16-bit value and then performs conditional logic based on comparisons. It checks whether a condition is met and updates the VM instruction pointer accordingly. Based on its behavior, this instruction appears to act like a conditional jump.

Compare Instruction

After that, another instruction was identified which performs comparisons between values.

Stack Operations

Two instructions handle stack management:

- Push: Pushes values onto the VM stack

- Pop: Pops values from the VM stack

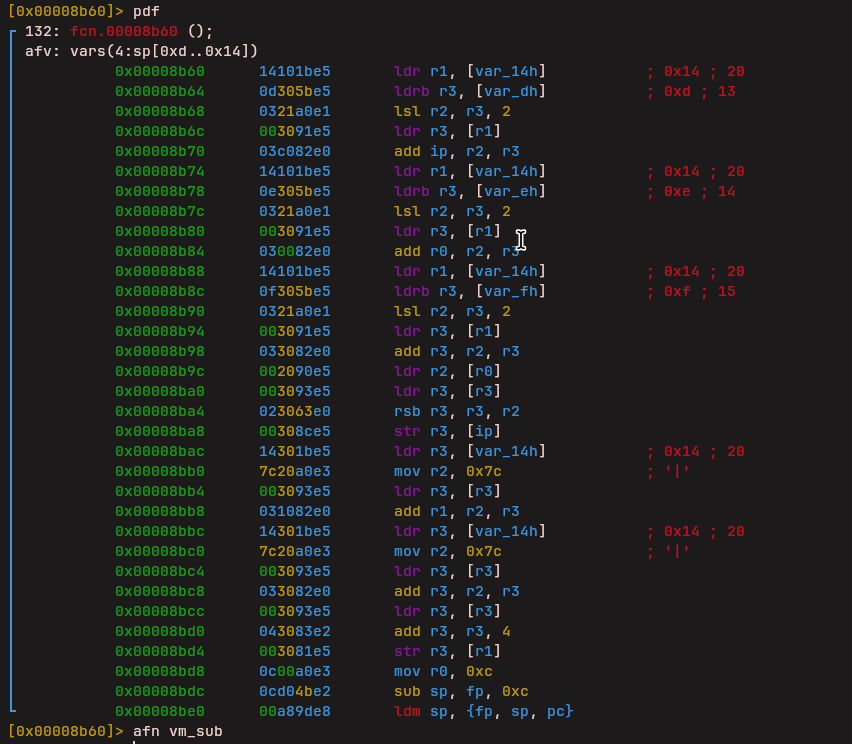

Subtraction (vm_sub)

Another instruction performs subtraction between values.

Bit Shifting

This instruction was more math-heavy and performs bit shifting operations before producing a result.

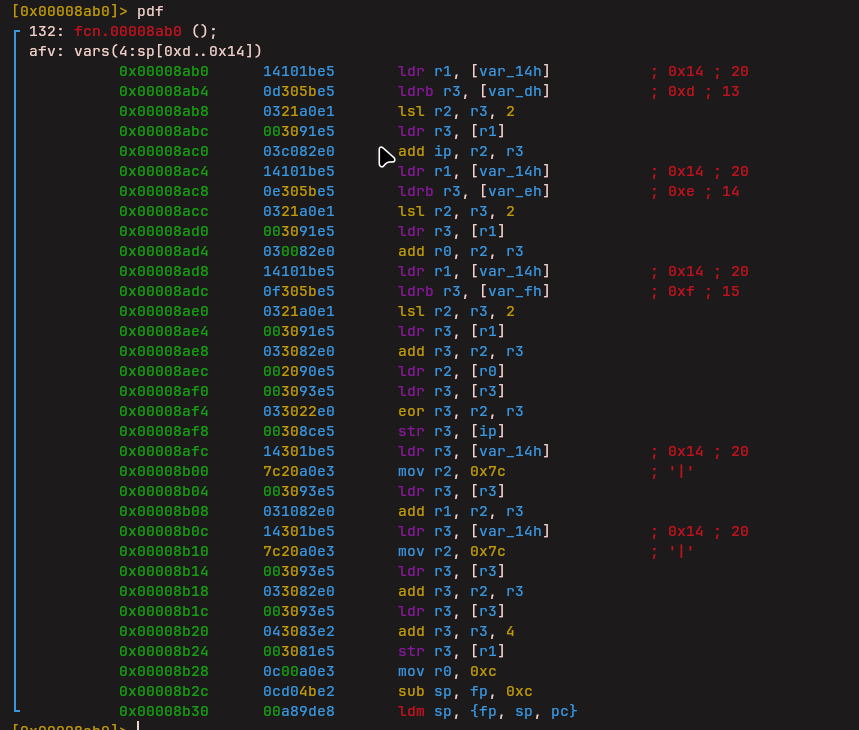

XOR Operation

The next instruction performs an XOR operation.

NOP

Finally, this instruction does nothing and serves as a NOP.

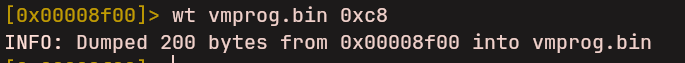

The Opcode Table

After finally renaming all the VM instructions in radare2, I ended up with a clear structure of how the virtual machine works internally.

I also identified the main VM dispatcher, which is responsible for fetching each instruction, decoding the opcode, and jumping to the correct handler.

Since the opcode handlers were already renamed and understood, I mapped out the full opcode table.

With this information, the extracted VM bytecode could now be mapped properly, because we know what each register represents and what each instruction does.

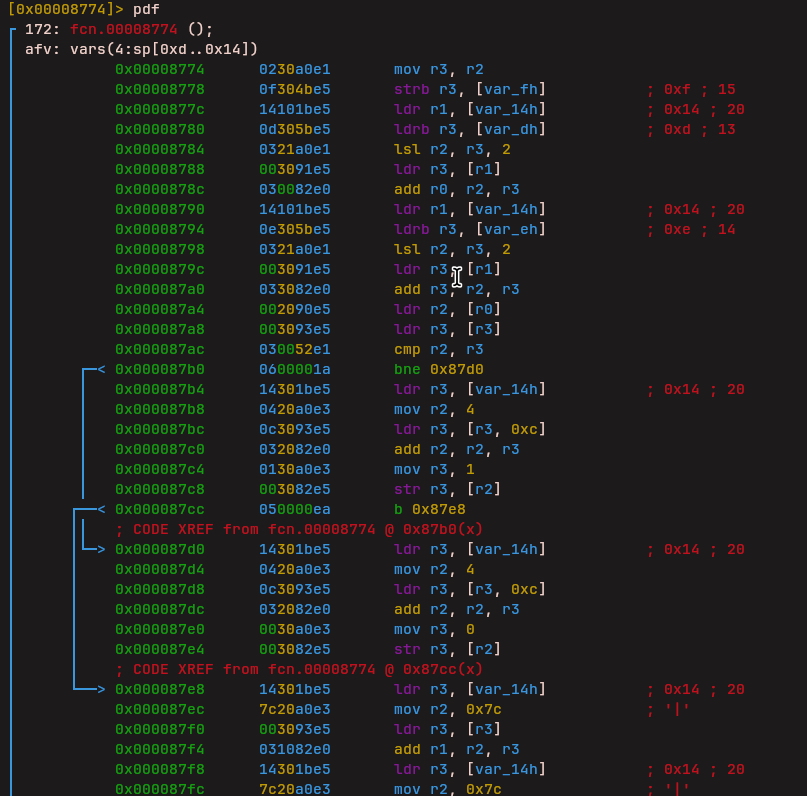

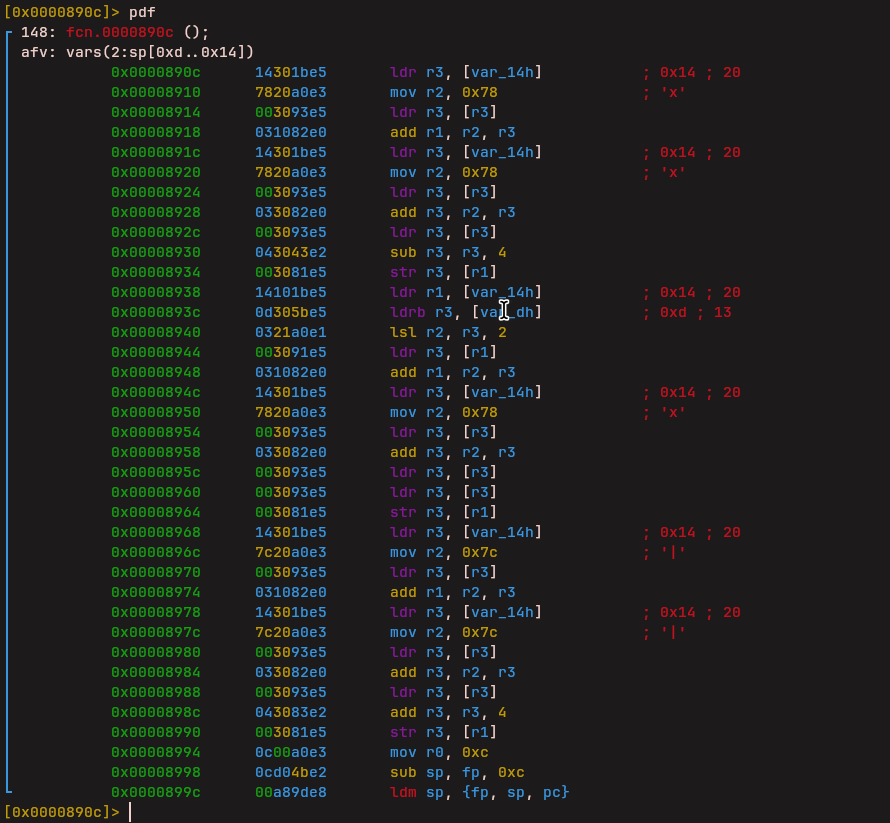

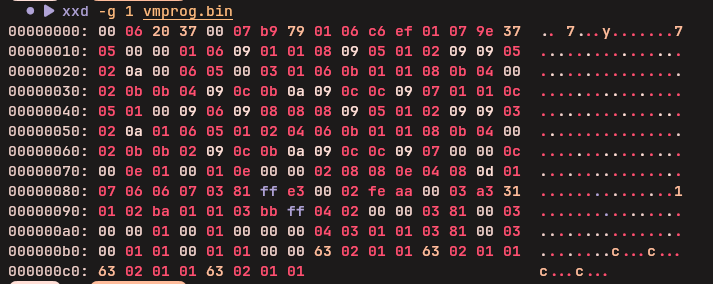

Discovering TEA Encryption

At this point, the next goal was figuring out how to convert this raw bytecode dump into readable pseudocode.

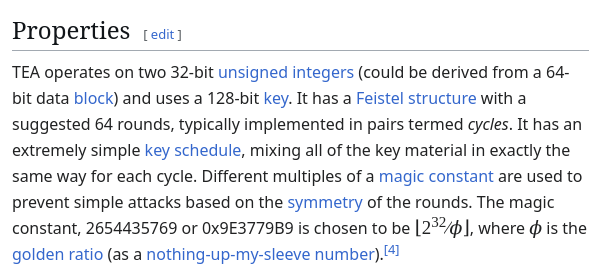

When the VM starts running, it first loads two constant values. One of them is 0x9e3779b9, which is a well-known constant used in the TEA (Tiny Encryption Algorithm) encryption algorithm. This immediately hints that some kind of encryption or mixing logic is involved.

The Algorithm

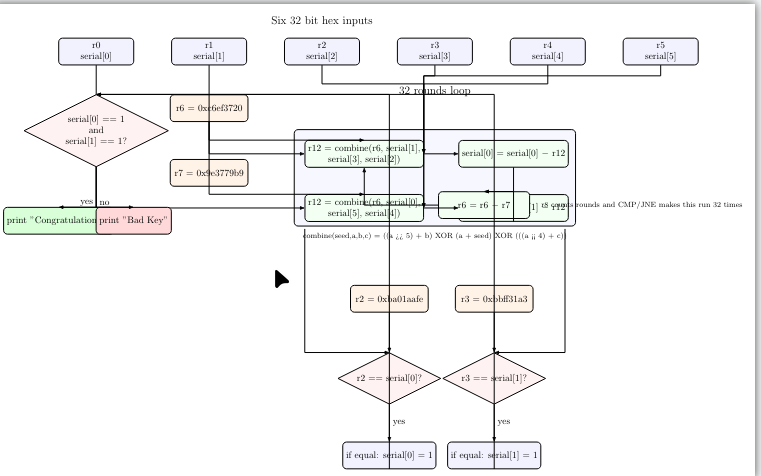

Instead of explaining everything line by line, the image below gives a clean high-level view of what the VM is actually doing.

In short, the program takes your input key and scrambles it using a small encryption-like routine that runs for 32 rounds. After all rounds are done, the final result is compared against two hardcoded secret values. If the values match, the key is accepted.

Keygen Solution

To solve this, I wrote a keygen in Rust that reverses the TEA encryption process:

use rand::Rng;

fn combine(seed: u32, a: u32, b: u32, c: u32) -> u32 {

let r9 = a.wrapping_shr(5).wrapping_add(b);

let r10 = a.wrapping_add(seed);

let r11 = a.wrapping_shl(4).wrapping_add(c);

r11 ^ r10 ^ r9

}

fn validate(mut serial: [u32; 6]) -> bool {

let mut r6 = 0xc6ef_3720u32;

let r7 = 0x9e37_79b9u32;

for _ in 0..32 {

let r12 = combine(r6, serial[0], serial[5], serial[4]);

serial[1] = serial[1].wrapping_sub(r12);

let r12 = combine(r6, serial[1], serial[3], serial[2]);

serial[0] = serial[0].wrapping_sub(r12);

r6 = r6.wrapping_sub(r7);

}

serial[0] == 0xba01_aafe && serial[1] == 0xbbff_31a3

}

fn keygen() -> [u32; 6] {

let mut serial = [0u32; 6];

serial[0] = 0xba01_aafe;

serial[1] = 0xbbff_31a3;

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

serial[2] = rng.gen::<u32>();

serial[3] = rng.gen::<u32>();

serial[4] = rng.gen::<u32>();

serial[5] = rng.gen::<u32>();

let mut r6 = 0x9e37_79b9u32;

for _ in 0..32 {

let r12 = combine(r6, serial[1], serial[3], serial[2]);

serial[0] = serial[0].wrapping_add(r12);

let r12 = combine(r6, serial[0], serial[5], serial[4]);

serial[1] = serial[1].wrapping_add(r12);

r6 = r6.wrapping_add(0x9e37_79b9);

}

serial

}

fn main() {

for _ in 0..100 {

let s = keygen();

assert!(validate(s));

println!(

"{:08x},{:08x},{:08x},{:08x},{:08x},{:08x}",

s[0], s[1], s[2], s[3], s[4], s[5]

);

}

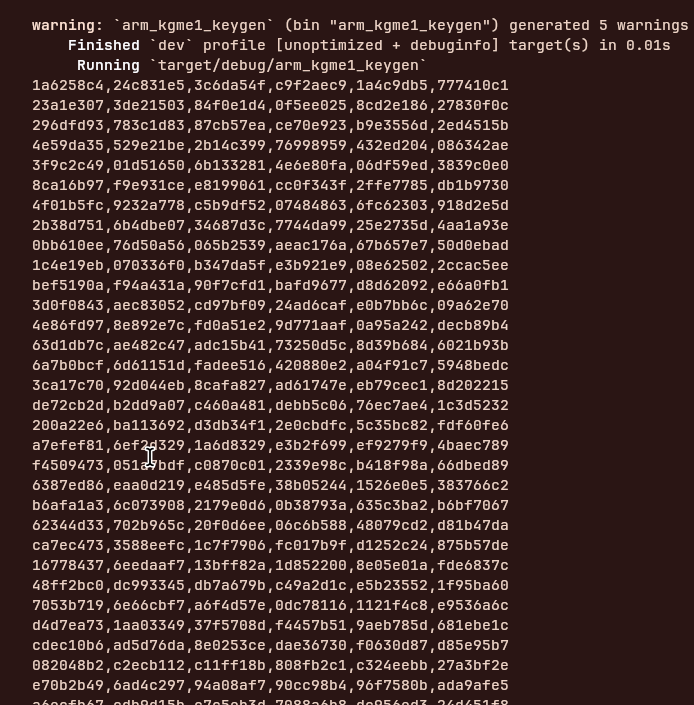

}The keygen generates valid serials by:

-

Starting with the target values (

0xba01aafeand0xbbff31a3) -

Generating random values for the other four registers

-

Running the TEA algorithm forward for 32 rounds

-

The resulting values become valid input keys

This challenge was a great exercise in reverse engineering a custom virtual machine and understanding classic encryption algorithms!